On a stage long darkened, a light still glimmers

Wellesley’s Group 20 Players

Peter Golden writer

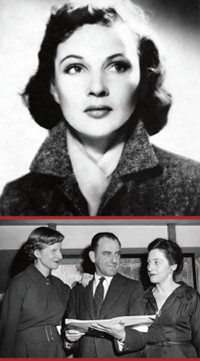

Photos courtesy of Wellesley College Archives

For those who have never been initiated into the special pleasures of theater, the intriguing world of the imagination known as “the drama” remains a mystery.

For those who have never been initiated into the special pleasures of theater, the intriguing world of the imagination known as “the drama” remains a mystery.

Why should one care for Shakespeare or Sondheim, anyway? And who were Chekhov, O’Neill, and Williams – a group of folksingers?

If you have never seen Paul Schofield agonize over his fate as King Lear or watched Vincent Gardenia writhe in self-revulsion in A View from the Bridge, then what’s the big deal? One can always pick up a video at Blockbuster, right?

Such has not always been the case in Wellesley and Weston, nor is it so today. Even now a local group, the Wellesley Players, stages its productions in a jewel box the equal of any small performance space in the world – the theater at the Sorenson Center for the Arts on the campus of Babson College.

The Weston Friendly Society (its name is a quaint artifact of the group’s 19th-century roots as a benevolent organization – a role it still faithfully fulfills) makes the rafters shake with applause in the upstairs auditorium of Weston’s Town Hall. Both groups have devoted followings, onstage and off.

A Special Part

Wellesley College has a special part to play in the world of local drama, too. Nora Hussey leads a full-fledged theater arts program, complete with professional actors and highly-regarded productions staged throughout the school year and into the summer months. Next year Wellesley will boast a brand-new performance center of its own.

But theater, like its siblings in the performing arts, dance and music, is ephemeral. Five minutes after the curtain rings down, the most hilarious comedy or compelling drama begins to waste away in memory.

But theater, like its siblings in the performing arts, dance and music, is ephemeral. Five minutes after the curtain rings down, the most hilarious comedy or compelling drama begins to waste away in memory.

Size matters, too; the trained personnel, money, and pure inspiration – not to mention the copious amounts of chutzpah required to even begin to approach the ramparts of world-class theater – are rarely found north of 42nd Street.

Rarely, but not always, as those with long memories and a taste for artistic adventure may recall from those far off days in the 1950s, when the Wellesley College campus could rightly lay claim to being called “The Epicenter of American Summer Theater.”

As scores of laudatory reviews (by no less an eminence than Elliot Norton, dean of New England critics), audiences in the thousands, legions of supporters, and a star-studded series of playbills attest, not just one but a whole series of magical moments occurred in the midst of an ambitious series of superbly costumed and set theatrical productions never equaled in these parts before or since.

Sound improbable? Then you’ve never met Alison Ridley, the daughter of a famous Oxford don, who traveled to this country with her American-born mother in 1940 to escape the distinct possibility of a Nazi invasion of England and never did go back to dear, old Albion.

Invoking the Muse

Invoking the Muse

Despite the vicissitudes of old age, Ridley is still able to invoke the muse in her room in a local assisted living facility. In summoning up a whole trunk-full of memories, her recollections are so improbable as to suggest her dry sense of humor and quick repartee are but a cover for an overly inventive mind. Documented fact proves otherwise.

Ridley’s predisposition to modesty and understatement notwithstanding, her memory, as confirmed by the voluminous archival collections of the Wellesley College library, is clear as a bell.

The middle years of the 20th century may be rapidly receding in time and our collective memory may grow dim, but in the annals of American theater Alison Ridley stands as a talent of the first rank – a living testament to the power of spirit and imagination as conveyed through the medium of the drama.

The fact that Ridley and the Group 20 Players at the Theatre on the Green are largely forgotten speaks more to changing tastes and the advent of digital technology. But the hundreds of patrons, actors, designers, costumiers, set builders, lighting technicians, and crew that together staged upwards of 50 major productions in seven iridescent Group 20 seasons at Wellesley College are still remembered, if only by a few. Among them is Robert Brustein, who can justly be called the dean of American theater.

Brustein is founder of the American Repertory Theatre at Harvard, where he has taught for decades. As theater critic for The New Republic and a widely-published journalist and social commentator, he has fond memories of the Group 20 Players at Theatre on the Green, and for good reason: He began his career there.

One of the First

“It was an extraordinarily good classical repertory company, one of the first after the war,” says Brustein in a phone interview. “It formed a lot of my opinions about what theater should be. It was my apprenticeship in professional theater and made me dedicated to company work, which to me is the highest form of artistic endeavor in the theater.”

In gathering his memories from half a century ago, Brustein pays tribute to the great character actors with whom he worked in his first roles, including Rosemary Harris, Fritz Weaver (“gentle and tremendously talented”), Robert Evans – briefly Alison Ridley’s husband (“a great actor who quit the business to teach philosophy; he was always talking about the basis of ‘reason’ ”) – and the late, widely-recognized Nancy Wickwire, who died tragically in middle age of cancer.

In gathering his memories from half a century ago, Brustein pays tribute to the great character actors with whom he worked in his first roles, including Rosemary Harris, Fritz Weaver (“gentle and tremendously talented”), Robert Evans – briefly Alison Ridley’s husband (“a great actor who quit the business to teach philosophy; he was always talking about the basis of ‘reason’ ”) – and the late, widely-recognized Nancy Wickwire, who died tragically in middle age of cancer.

“But also let me pay tribute to Alison,” Brustein says. “She found Group 20 limping and helped it to its feet. In those days she had us doing everything. She used to call me Eeyore (a character in Winnie-the-Pooh) because I played the role in a radio production she staged.”

Back in the late 1940s, when Group 20 was still in its infancy in Union, Connecticut, Alison Ridley came to the company with theater in her blood. “As a child I staged productions of Peter Pan,” she says in a voice still clear and beautifully measured. “I got my mother and father to participate,” she adds. “My dad was Captain Hook, but I made sure I always played Peter.”

Toward the end of Group 20’s days in the summer of 1959 (more on that sad climax later), Ridley went so far as to convince the renowned character actress Rosemary Harris (with whom Ridley is still in touch) to take the role of Peter Pan in the production of the same name.

Fabulous Showmanship

Malfunctioning flying wires left Harris dangling in mid-air on some nights, but fabulous showmanship and Harris’s vast talents overcame even that glaring deficit and brought rave reviews.

Like her American-born mother and younger sister, Ridley graduated from Wellesley College (Class of 1951) and went to work, finding employment with John Davis Lodge, then governor of Connecticut and brother of Henry Cabot Lodge. But it turned out that a career in political speechwriting was not exactly Ridley’s cup of tea.

By 1953 she had brought Group 20 home to Wellesley College after a season in Puerto Rico. As an undergraduate, Ridley had been attracted to theater courses taught by Eldon Winkler, head of the Wellesley theater department in the late 1940s. Like many other undergraduates, she followed him to Connecticut in the troupe’s first years, when it took its name from the number of its original incorporators.

To Betty Ann Metz (Wellesley Class of 1949) must go the honor of being founding director, along with credit for documenting the company’s early years. Then, lightning struck. With the support of Margaret Clapp, president of the college, the troupe came home to its alma mater. Hay Amphitheater was chosen as its regular performance venue. This outdoor facility possessed all the caché of timeless design and surprisingly good acoustics, and its grassy stage and shrubbery backdrop accommodated plays like A Midsummer Night’s Dream beautifully.

Prodigious Undertakings

Prodigious Undertakings

A series of prodigious undertakings commenced, leading to seven seasons of extraordinarily challenging and even provocative drama.

From the classics were chosen Much Ado About Nothing and A Midsummer Night’s Dream and from the modern repertory A View from the Bridge and The Crucible, the latter two by special permission of Arthur Miller after Ridley tracked him down in New Jersey. And there was more – much more. The Shoemaker’s Daughter featured a young Jerry Stiller (of Seinfeld and King of Queens fame). Rosemary Harris, a superb character actress since the 1950s, took leads in Much Ado About Nothing and any number of other classics.

Ridley had an eye for quality, and always recruited the best. Hordes of sponsors were rounded up out of local business and social circles. Offers went out to other rising stars (and were almost always accepted), ranging from Harris, Brustein, and Weaver to the wildly ribald Stiller. Also in the company at one time were Martyn Green (of Gilbert & Sullivan fame), Nancy Wickwire (called the most talented young character actress of her generation) and even Ireland’s favorite son, Tom Clancy (of Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem fame).

Tharon Musser, who would go on to become dean of Broadway’s lighting designers with over 150 major productions to her credit, served as Ridley’s production assistant for a season. And then sadly, as can often be the case in the theater, disaster struck like a soaking rain on a calm summer’s day. The financial bottom fell out for the company.

Hopelessly Ensnared

In the summer of 1959 it was discovered that Group 20 was up to its ears in debt. Ridley, who lived by the axiom of “art first, budget later,” found her beloved troupe was hopelessly in debt to the tune of $35,000 – no mean sum at a time when a similar amount would buy a comfortable mansion.

Calls were made, appeals launched, and a note was inserted in one of the very last Group 20 playbills, but to no avail. The lights dimmed and then died at the Theatre on the Green, Wellesley College. A competing company opened on the banks of the Charles River in Cambridge featuring Sir John Gielgud in its premier production.

Yet, a new era in American theatre began soon afterward, with resident companies (one at Yale founded by Robert Brustein) popping up all over the country. Jerry Stiller paired with a partner and became a comedy legend. Tom Clancy joined Tommy Makem and took the Newport Folk Festival by storm.

Alison Ridley went on to produce the Boston Arts Festival, creating performances as brilliant as ever in the Boston Public Garden.

A dozen file boxes in the Clapp Library archives at Wellesley College still brim with the magic of those seasons of long ago, barely containing a quotient of magic too long hidden away. And on a stage long darkened, a light still glimmers.