Our Neighbors’ Untold Stories

A visit to a seniors’ home unlocks decades of memories

Steve Maas writer

Peter Baker photographer

We would like to introduce you to three people. They have touched hundreds, if not thousands of lives. But odds are you never have heard of them.

They all happen to be residents of Epoch Senior Health of Weston. Each arrived at 75 Norumbega Road by a different path, several stretching back to the waning days of the First World War.

One helped bring electricity and communications to islands off Alaska and the French West Indies, another recalls searching for a job in Depression-era Boston and being turned away because she was a Protestant and not a Catholic, and the third worked with a gas mask at her side at MIT on a chemical warfare project during the Second World War.

But those experiences aren’t why they are being profiled. We simply approached Epoch and asked for residents willing to look back on their lives. Mike Koulopoulos, Mary Frances Daly, and Barbara Stewart answered our call.

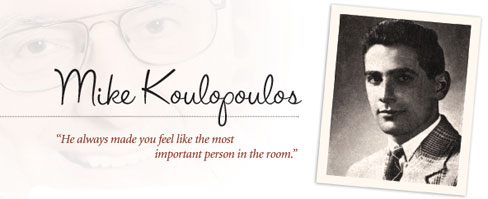

The headline reads “Waltham Wins on Koulopoulos-to-Gregorecus Pass.” Beneath it is a breathless account of quarterback Mike Koulopoulos pitching the football to Jim Gregorecus, who scampered 18 yards for a touchdown.

Mike Koulopoulos would make headlines many more times as he led the Waltham High School Wildcats to the Eastern Massachusetts Class A Championship in 1943, but in retrospect no other would be as poignant as this one.

Koulopoulos connected with Gregorecus again some 60 years later, this time as roommates at Epoch in Weston. The pair, both suffering from Parkinson’s disease, remembered each other. “Hi Slim,” Mike said to his long-ago receiver. And when a visiting priest asked who had been the better player, each pointed to the other.

That show of modesty would come as no surprise to Mike’s family and friends. When his dad would boast at family gatherings about football games, Mike would kick him under the table. He didn’t want his younger brother, the team manager, to feel overlooked.

Born in Lowell in 1925 to a cobbler and a mill girl, Mike was the first of three children. His parents emigrated from the Greek mountain village of Lagadia, but didn’t meet until they were in America. When Mike was a year old, the family moved to Waltham, where his dad set up shop on Main Street and bought a two-family house on Fiske Street.

Playing quarterback and short stop for his high school teams, Mike made the Koulopoulos name famous in Waltham. But by carrying that fame lightly, he endeared himself to his classmates, who elected him their president. Girls especially were struck by his politeness, and the way he’d always say “good morning” in the hallways. His son John, who would become a football star as well, learned about his dad’s triumphs from newspaper clippings and the recollections of schoolmates. When John asked his dad about his high school days, he’d deflect the question. “He would always bring the conversation back to you,” says John. “He always made you feel like the most important person in the room.”

Playing quarterback and short stop for his high school teams, Mike made the Koulopoulos name famous in Waltham. But by carrying that fame lightly, he endeared himself to his classmates, who elected him their president. Girls especially were struck by his politeness, and the way he’d always say “good morning” in the hallways. His son John, who would become a football star as well, learned about his dad’s triumphs from newspaper clippings and the recollections of schoolmates. When John asked his dad about his high school days, he’d deflect the question. “He would always bring the conversation back to you,” says John. “He always made you feel like the most important person in the room.”

Mike was off in the Navy when his high school class celebrated graduation. He didn’t see action, but he did gain an interest in communications and wiring. After he was discharged, he studied engineering at Northeastern University and, because his scholarship depended on it, returned to the football field. Weary from hours of practice, he would ride the trolley to Watertown and then a bus to Waltham, where he faced a grueling night of homework.

As part of the university’s work/study program, Mike took a job with Simplex, a wire and cable company then based in Cambridge. He would work there the next quarter century, starting out in the lab designing cable for transmitting communications and electricity, then working in the field overseeing its installation. He wired islands off of Alaska and in the Caribbean, and he traveled halfway around the world to China and Japan. He rose through the ranks, establishing a reputation for thoroughness, coolness, and decisiveness.

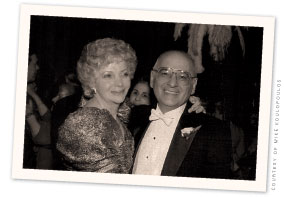

“Mike said the biggest problem is that people are afraid to make decisions,” says his wife, Anita. Mike may have been methodical in business, but not in matters of the heart. One Valentine’s Day, well into their now 56-year marriage, Mike bought Anita a small bust of a man and woman together cheek to cheek. The shopkeeper later told her, “I never saw a man put so much time and thought into selecting a gift.”

“Mike said the biggest problem is that people are afraid to make decisions,” says his wife, Anita. Mike may have been methodical in business, but not in matters of the heart. One Valentine’s Day, well into their now 56-year marriage, Mike bought Anita a small bust of a man and woman together cheek to cheek. The shopkeeper later told her, “I never saw a man put so much time and thought into selecting a gift.”

The couple married in June 1953. John was born in 1955 and a second son, Jim, about a year later. Over the years, the family moved six times, living in Sudbury for 28 years before Mike went into nursing care at Epoch. Mike’s job would take him away from home for weeks sometimes, but he made every effort to attend John’s football games in Wayland and later Hampton, New Hampshire.

Jim, who inherited his father’s mechanical side, says he always felt he got equal time. Now a builder, he says his father helped him work with tools on his childhood construction projects. The boys had an elaborate model train in the basement. Meanwhile, Mike was overseeing the wiring of full-size locomotives, as well as oil rigs and factories. He wound up his career as vice president of operations at Surprenant, then a Clinton-based division of ITT.

“Mike was the ultimate team player,” says Stanley H. Straube, then Surprenant vice president for administration. And John C. Armacost, then-president of Suprenant and Mike’s former boss says, “You think of most manufacturing guys being hardnosed; he could be tough but in a nice way.”

Mike retired from Suprenant in 1989. The Parkinson’s symptoms began to appear over the next decade, whittling away at his faculties. But Mike’s devotion to his family remains, as does his charm. Asked how many girlfriends he had as a popular young athlete, he doesn’t hesitate.

“Only one,” he says, and he points to Anita.

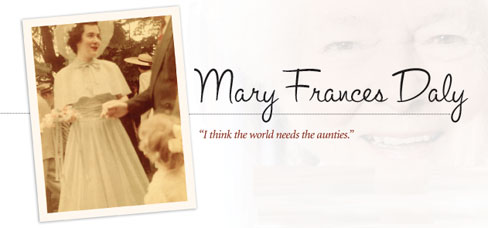

In some ways, her story resembles that of Jimmy Stewart’s character in It’s a Wonderful Life.

A devoted daughter helps care for her younger siblings through the Depression and World War II. She watches as one by one they go off to college, war, and eventually lives of their own. Meanwhile, she stays behind and minds the home front.

But while the life of Mary Frances Daly may not have turned out to be like that of George Bailey, it has been wonderful in its own way. Real life, after all, is not “reel life.” It’s much more complicated—and much more interesting.

Fran—as she is known in the family—didn’t marry, but to dozens of children she was like a second mother. She didn’t strap on a helmet, but she helped fight World War II. Her most important accomplishment, though, has been providing the glue that has bound the Daly family down through the generations.

To understand Fran’s story, you have to journey back to Montreal in the mid-1920s. Her father, William Daly, a civil engineer, had just lost his wife. She died after giving birth to twin girls, only one of whom survived and just barely at that. Fran was the second oldest of four other siblings, all under 10. Friends and family offered to take them in, but William refused.

Today, the remaining Daly children—Fran and her two younger brothers—remain close. Fran has 15 nieces and nephews, 23 grandnieces and nephews, and 3 great- grandnieces and nephews. As matriarch, she has passed along the Daly story and her father’s devotion to family. It’s a role she relishes.

“I think the world needs the aunties,” Fran says. “Aunties can spoil the children and love them—and wash their hands and go home.”

Home for all but a dozen of her 90 years has been a modest four-bedroom shingle house in Newton, just a few blocks from Brighton’s Oak Square. Fran’s father bought the house in 1929. He had just remarried after moving the family to Boston to be closer to a widowed sister. His new wife became pregnant and delivered a boy. The son survived, but not the mother. Again, Fran’s dad was a widower. With great reluctance, he accepted an offer from the sister of his late wife to raise the boy. Fran and her brothers and sisters didn’t get to know their half brother until after their father died.

For several years, all but the youngest of the Daly children boarded at the Academy of the Assumption in Wellesley Hills, now the site of MassBay Community College.

For several years, all but the youngest of the Daly children boarded at the Academy of the Assumption in Wellesley Hills, now the site of MassBay Community College.

But with the Depression, Fran’s father lost his job, and he wanted his children to be home with him. He told the family’s housekeeper that he couldn’t afford to pay her until he got a job, but she stayed on anyway.

Fran’s brother Bill Daly, who lives in Concord, recalls that all the kids had to pitch in. Fran and her sister Helen, who was a year older, helped keep the younger kids in line. Brother Dick Daly of Arizona recalls that he would turn to Fran if he had a problem. “She always took care of our needs when we needed her the most,” he says.

After graduating from Newton High School, Fran went to a two-year business school. “She would have gone so much further had she been able to go to college,” Dick says, “but I think she had to sacrifice that opportunity to allow the rest of us to get there.”

Still, the secretarial skills she learned—shorthand, typing, and managing an office—would pay dividends over the next 50 years. After working for a real estate firm and the state unemployment office, she landed a job at MIT. The war was looming, and Fran was about to play her role in it.

In addition to a typewriter, Fran’s desk came with a gas mask. Her office was at a lab that did research into chemical weapons for the Army. “We weren’t supposed to tell who we worked for,” she says. As a precaution for gas leaks, the lab had a canary in a cage. “If the canary died, they’d say everybody out of the building,” Fran says (not that she can recall that happening).

With the war’s end, Fran lost her MIT job, but she put off searching for another one at her father’s request. He wanted her to help run things at home and prepare for a Christmas reunion. “It turned out to be the last Christmas that he lived,” she says.

Although her brothers say she had many suitors, Fran remained single. She thinks things may have turned out differently were it not for the war. “If they hadn’t all gone off, I would have probably married,” she says.

Fran later returned to MIT, where she ended up as the assistant to the vice president for finance. Her brother Bill says she also applied her organizational skills to keeping track of her growing number of nieces and nephews.

But age eventually takes its toll, even on people as feisty as Fran. She has had two hips replaced and undergone heart bypass surgery. In 2007, she moved into Epoch. Her family regularly visits—the out-of-towners sometimes stopping by even before seeing their own parents. Fran still wants to hear all their latest news, though they have to speak up more loudly now.

“You can learn things from some old people,” Fran says, referring not to herself but to a former neighbor who lived to be 102. When Fran would complain about some situation out of her control her neighbor “would say, ‘don’t get a wrinkle.’ And she had this nice skin. No wrinkles.”

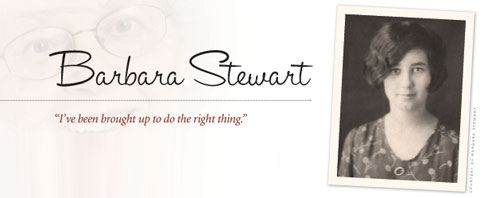

It happened decades ago, but Barbara Stewart remembers vividly when she was called on the carpet in her boss’s office at Standard Oil.

Barbara’s job was filling orders from gas stations for tires, oil, and other auto parts. Her misdeed was calling station owners to remind them of free merchandise they had earned through a buyer’s incentive program. The men from sales felt Barbara was overstepping her bounds; she was costing the company money. But Barbara stood her ground. “I’ve been brought up to do the right thing,” she declared. “I’m going to continue doing it.” And no one dared stop her.

“Barbara was very forceful, and she knew what she wanted,” says one of her younger sisters, Kay Dick of Needham. Barbara usually accomplished what she wanted, despite the abundance of obstacles life has thrown in her path—health wise and otherwise—the last 90 years.

The family moved to a house on School Street in Watertown, not far from the Charles River, in 1922. Barbara was four and her sister, Peggy, 16 months older; two sisters were yet to be born. Barbara would live there for the next 80 years, watching fields and trees being cleared to make way for houses and businesses.

Barbara jokes that she used to think her dad, Jimmy Stewart, was the movie star. Actually, he was a carpenter, though work was hard to find during the Depression, when many of their friends lost their homes. After graduating high school in 1937, Barbara spent a year hitting the sidewalks of downtown Boston. When she applied at the telephone company, one of the first questions on the form asked for religion. “I saw them throw my application in the wastebasket,” she says, adding that the same thing happened to her sister. Barbara, a Presbyterian, says a relative who worked at the company told her only Catholics were being hired.

Barbara finally got a job as a “bundle girl” at C.F. Hovey, a department store that was later bought out by Jordan Marsh. She earned $14.50 a week for 40 hours of wrapping drapes and linens in brown paper secured with twine. She was rescued by World War II, when she got a job in the payroll office at the Watertown Arsenal, just blocks from her home. That sprawling weapons complex has since been transformed into stores, offices, and restaurants.

After the war, Barbara went to work for Standard Oil, the company today known as Exxon/Mobil. The incident with the sales manager aside, she thrived at the company. Her office and administrative skills were so valued that her bosses asked her to move to Pelham, New York, when the company transferred much of its operations there. She declined. “I felt that my duty was at home,” she says.

After the war, Barbara went to work for Standard Oil, the company today known as Exxon/Mobil. The incident with the sales manager aside, she thrived at the company. Her office and administrative skills were so valued that her bosses asked her to move to Pelham, New York, when the company transferred much of its operations there. She declined. “I felt that my duty was at home,” she says.

Her mother suffered from arthritis so severe she required crutches much of her life. Barbara and her sister Peggy, who also was living at home, spent much of their weekends doing chores around the house. “I had no qualms,” Barbara says about sacrificing so much of her own life to care for her parents. But looking back, she thinks of the might-have-beens, such as the young man she felt close to who was lost in the war. And she wonders, too, if she may have scared off a few fellows. “I might have been too cold,” she says.

That’s not how her nephew Stewart Dick describes her, though. “She is very warm, very caring,” he says, recalling how his aunt would tuck him in with a hot water bottle when he spent vacations at her house while in grade school. Barbara and Peggy, who died in 2000, used to take their nieces and nephews on trips (Barbara took Stewart to visit a sister in Iran) and their families out to dinner.

Nearly two hours into an interview with Barbara, she talks about the toughest part of her life. She estimates she’s had nearly 40 operations. The first—for kidney stones—was when she was just a teen-ager. “All along she’s had problems,” her sister Kay says. “I’d say to her that I thought you’d be the first one to go, but now I think she’ll outlive all of us.” Barbara has endured breast cancer surgery and operations on her back, gall bladder, and eyes. But it was her arthritic knees that forced her into the nursing home. She says she last walked without aid on January 24, 2006, just before she went in for a knee replacement. But the surgery failed and her knee became infected.

Barbara was determined to get back on her feet. From the day in August 2007 that she arrived at Epoch, she says, “I wouldn’t let anything interfere with my therapy.” David Tscherne, her therapist at the time, says that “Barbara … pushed herself farther than even I expected her to. On June 15, 2007, she celebrated “graduation day:” She got up from her wheelchair and, leaning on a walker for stability, strode down the hallway.

In a sense, Barbara has launched a new career at Epoch. Through her example and words of encouragement, she helps her fellow residents persevere in the painstaking process of rehabilitation. “She brings a great presence to the floor,” Tscherne says. And she brings faith, says Kevin Campbell, a pastoral associate for Newton Presbyterian Church, where Barbara has been a member for more than half a century. Visiting Barbara, he says, “makes my day.” Campbell recalls an Epoch resident pointing to Barbara and saying: “She inspires us all to just keep going.”