River Towns are Winged Towns

Peter Golden writer

Photography courtesy of David Parish and the Massachusetts Audubon Society

Fall holds a promise all its own. You can sense it in the first light of morning. The sky is bluer, one’s sense of possibility grows, the air turns rich with the ripening promise of the harvest season.

Fall holds a promise all its own. You can sense it in the first light of morning. The sky is bluer, one’s sense of possibility grows, the air turns rich with the ripening promise of the harvest season.

Along Route 128 such thoughts are lost as the inevitable repetition of the morning rush hour plays out. Who even notices the changing seasons or the Charles River, flowing unobtrusively by the side of the highway? Who sees the flocks of migratory wildfowl scattered along the river’s course, masked in morning mist?

Highways and office parks have almost overwhelmed the Charles River, yet its picturesque charm remains. Time and intention have placed the Charles largely out of sight and mind, hidden in Wellesley’s back yards and office parks. In Weston, in what once were pasturelands now put to use as a golf course, the river maintains a better purchase before disappearing under Route 128, again, and ducking around a bend into Newton.

But rivers, even forgotten ones, are timeless. They endure. Henry David Thoreau knew this. In resonant phrases jotted in the mid-19th century, he espoused their unrivaled beauty and enduring value. His words still resonate, as timeless as the New England landscape:

“There is something in the scenery of a broad river equivalent to culture and civilization … A river is superior to a lake in its liberating influence. It has motion and indefinite length. A river touching the back of a town is like a wing. It may be unused as yet, but ready to waft it over the world. With its rapid current it is a slightly fluttering wing. River towns are winged towns.”

These days the “fluttering”of the Charles River is slight indeed, at least in its first appearance in Wellesley along the western border of the town. There the Charles, notorious for its serpentine wanderings, fades quietly into other communities as it flows placidly toward Needham and Dover.

Out of sight

Out of sight

Unexpectedly, the Charles reappears miles away to the east at the opposite end of town, overwhelmed by highways and bridges, but filled with surprises and rare rewards for those who know where and how to look. Father Skehan of the Weston Observatory offers a brief geology lesson: “The Charles is basically the remnant of the runoff from a glacier—melt water extending arc-like around an ice sheet which began a slow retreat from the Boston area about 11,000 years ago. It left behind a shallow outflow that the local Indians, who moved into town soon thereafter, called Quinobequin, or “river that turns in upon itself.”

The meager presence of the Charles in Wellesley, the study of local geology aside, stems from matters of property rights, which our ancestors pursued well into the later 19th century with all the competitive energy and pride of possession they could muster. In separating itself from Needham in 1881, Wellesley won much, but not all; the river was kept out of the bargain.

Dramatic reappearance

Next to a quaint, little stone shed (some say it is the last remnant of the Boston to Worcester stage coach line supplanted by the railway in the early 19th century), the Charles surges back into Wellesley at Hemlock Gorge before plunging over a horse shoe-shaped dam and disappearing under Route 9.

Momentarily it appears a hundred yards to the north on the other side of the highway, beginning a one-mile traverse along a course masked by office parks and well-treed riverbanks. Residents of River Ridge Road in Wellesley can see this section of the Charles in winter as they look east across Route 128. Earlier in the year, there are other sources of color here. Mass Audubon staff ornithologist Simon Perkins expands on them: “By mid-May in spring migration time, the sky’s the limit along that section of the Charles, including Canada geese and mallards on the open water. On any given day you might see 50 other species, including wood warblers, scarlet tanagers, Baltimore orioles (which nest along the river), and more common species like black-capped chickadees (the state bird), blue jays and the ever-present American crow.”

“Great blue herons can appear at any time of year and in summer black-crowned night herons fly up the river from their rookeries on the Boston Harbor islands, using the Charles as a route along which to fish,” Perkins adds.

Soon, most species will head south or for more sheltered local quarters, but for now they revel in a feast of duckweed and summer-fattened fish.

This short, hidden passage of the river holds culinary pleasures for humans, too, according to Weston native Russ Cohen, an expert wild food forager and a river advocate employed by the state.

Found food

Years ago, as a student at Weston High School, Cohen first made a meal for himself from food found in the woods. His interest stemmed from a course called “Edible Botany,” and he has been rummaging around in the wild for nature’s bounty ever since.

“The Number One species I tell people to look for along the upper Charles is Japanese knotweed, a first cousin of rhubarb that looks like nothing so much as bamboo,” he says. “Cut and peeled right where it grows, it tastes vaguely like a Granny Smith apple.”

The progress of the river but a mile to the north finds the Charles making an abrupt turn before leaping with a lusty roar over Cordingly Falls. In the sharp light of a fall morning the cataract fragments into a myriad of glistening jewels. Here, as Wellesley historian Beth Hinchliffe informs us, the town’s industrial center once stood. “Saw mills, grist mills, silk and paper mills—all were present at Lower Falls,” she says.

While they are all long gone, a quaint footbridge of antique design spans the river above the falls. “It’s named for Mary Fyffe Hunnewell, who was quite a gal,” says Hinchliffe. “She was among the first of the great, local environmental activists.”

While they are all long gone, a quaint footbridge of antique design spans the river above the falls. “It’s named for Mary Fyffe Hunnewell, who was quite a gal,” says Hinchliffe. “She was among the first of the great, local environmental activists.”

If you have not seen Cordingly Falls yourself, or are a parent in need of an excuse to get the kids out of the house, do not hesitate to go there in any season or weather. This booming, boiling, misted torrent invites contemplation—and plenty of photos, too.

A stretch of rapids

Immediately below the falls, the Charles wheels about once again, its waters creating a stretch of rapids best seen from a small park beside the aptly named River Street. Here the Charles looks properly energetic, its waters leaping white and frothy over rocks and crags.

And then, in slipping over one more dam and passing under Washington Street, something magical happens: First, the river begins to slow as it enters into another world—a pastoral, peaceful place defined by quiet residential streets and, of all things, a golf course.

Alyssa Mickle, an attorney, relates how she was house hunting years ago when a real estate agent drove her along Boulevard Road, which is one of the few streets in Wellesley and Weston that fronts on the river.

A charming Arts & Crafts-style cottage built before the First World War entranced Mickle. “I want that one,” she exclaimed. The agent noted the obvious: it was not for sale. But the next morning she called, accusing Mickle of sorcery. Unexpectedly, the house had come on the market. Needless to say, Mickle had a bid in (that was soon accepted) by nightfall.

Further downstream, the Charles crosses over the Weston line and through the Leo J. Martin Golf Course. Florence Capobianco, who lives on a street behind Boulevard Road, has played golf there for years.

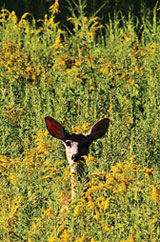

A doe and fawns

“Not so long ago my friends and I were in a foursome on the second hole and ready to tee off,” she recollects. “But we had to wait. A doe had stepped out of the woods with three fawns and stopped so they could nurse, right on the fairway.”

The golf course hosts more than the deer and legions of handicappers who come there every year to play. Hard by the side of the course’s main parking lot sits the headquarters of the Charles River Watershed Association (visit www.charlesriverwatershed.org.), whose members play a major role as advocates for the river.

The golf course hosts more than the deer and legions of handicappers who come there every year to play. Hard by the side of the course’s main parking lot sits the headquarters of the Charles River Watershed Association (visit www.charlesriverwatershed.org.), whose members play a major role as advocates for the river.

A monthly testing program at various checkpoints along the Charles brings Wellesley resident Margo Connor out at 6:00 am to drop collection buckets into the stream. Water she collects is bottled and shipped to a laboratory where it is checked for bacteria and sedimentation.

With a sharp eye toward illegal sewer connections and other forms of pollution, volunteers like Connor, a former Polaroid researcher and now a doctoral candidate in art history at Wellesley College, take samples of river water from the Cheney Footbridge at Elm Bank Reservation.

“I believe in the sanctity of this beautiful gift that happens to be part of our environment,” she says. “Depending on the season and time of day, the river reflects the trees and sky above it in ways that can be magnificent or very subdued. On even the stillest days you can still feel the rush of current beneath the surface; it’s one of the eternal mysteries of the river.”

Fishing the Charles

Another mystery lies with the fish to which the Charles is home. Ray Capobianco, Florence’s brother and a highly regarded local angler, occasionally casts his lines in search of an answer.

“I’m a trout fisherman,” he says, “and there are trout around Indian Springs Brook, which empties into the Charles, as does Stony Brook, in Weston. But if you really want to know about fishing the Charles, you’ll need to talk to David Kaplan,” he adds.

Half an hour on the phone is required to locate the author of the highly-regarded Fishing Guide to Middlesex County Rivers (Purgatory Cove Press, 1996). Kaplan, whose career spans such improbable occupations as building racecars and practicing Native American land law, reels off an impressive roster of fishing spots, species, and fishing techniques.

“Norumbega is an interesting place for largemouth bass and northern pike,” he says. “Pike can go up to 20 pounds around there and are a great fighting fish.”

Elsewhere along the Charles in Wellesley and Weston, Kaplan ticks off the places where giant carp are to be found— “Up to 25-pounders in some places,” he says.

Elsewhere along the Charles in Wellesley and Weston, Kaplan ticks off the places where giant carp are to be found— “Up to 25-pounders in some places,” he says.

As Kaplan recalls his favorite fishing spots, images come to mind of the Riverside Casino in the Lakes Region area of the Charles on Weston’s eastern-most border. A century ago lanterns glowed and banjos rang out on summer nights as young couples paddled canoes along the river. In the days before the Model T changed both transportation and courting habits, the Charles offered something rare to young couples: privacy.

Adaptive reuse

These days, with the Casino long gone, local discussion regarding the Charles centers on the adaptive reuse of an old railroad bridge connecting the Wellesley and Newton parts of Lower Falls. It is a controversial plan, but one very much favored by open space and recreation advocates.

Meanwhile, the river rolls on. Soon, the migratory flocks that settled along Quinobequin during the summer will head south and the roar of Cordingly Falls will diminish as a succession of dry, fall days diminishes the water flow.

“River towns are winged towns,” said Thoreau, and with such a graceful possession as the Charles River, Wellesley and Weston are truly blessed.

Peter Golden observes the American experience through the lens of local history.