Artist Profile

Sculptor Jamie Burnes

Winky Merrill writer

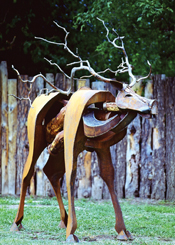

All an artist does is make strings of choices,” says Weston sculptor Jamie Burnes. In Burnes’ case, those choices result in abstracted animal forms, each with its own personality and attitude, ranging from life-sized horses, cows, bulls, and bears to smaller table pieces. His materials are fallen trees that he finds in the woods (locust is his preference but it can be hard to find) and COR-TEN steel–a stable alloy that does not flake or rub off when it oxidizes.

All an artist does is make strings of choices,” says Weston sculptor Jamie Burnes. In Burnes’ case, those choices result in abstracted animal forms, each with its own personality and attitude, ranging from life-sized horses, cows, bulls, and bears to smaller table pieces. His materials are fallen trees that he finds in the woods (locust is his preference but it can be hard to find) and COR-TEN steel–a stable alloy that does not flake or rub off when it oxidizes.

One of Burnes’ horse sculptures, Rich Sis, grazes near the entrance to the Weston Public Library. On loan for two years, the horse is a favorite of library staff and patrons according to Library Director Susan Brennan. “It fits the setting beautifully and reminds us of Weston’s farming heritage,” she says. “We wish we could keep it permanently.”

Last fall, two of Burnes’ bears were chosen for a temporary exhibit on the Rose Kennedy Greenway in Boston. He says, “When we loaded them up at the end of the show, someone came out of a nearby office building and protested, ‘Please don’t take the bears away!’” Betty Bothereau, owner of L’Attitude Gallery in Boston where Burnes shows his work, says, “We have seen a lot of interest in Jamie’s sculptures – they make everyone smile.”

Growing up, Jamie and his family raised horses, chickens, sheep, and bees. His father, Bear, worked for Earthwatch Institute and was involved with Land’s Sake and Green Power Farm in Weston. A love and respect for farmland and an agrarian lifestyle were instilled in Jamie –and these themes inspire his sculptures.

Down a serpentine driveway in Weston, after pavement gives way to gravel, Jamie Burnes’ unconventional home and studio appear. “It’s our own little vortex,” says Burnes, who still lives in the barn that was transformed into a home in the early 1970s by his father. With grey weathered siding and trapezoidal windows, it has a funky bohemian feel that is eclectic and welcoming. Burnes’ dog, Mosey, wags his tail when we enter the house, where evidence of a creative lifestyle abounds. The post and beam volume soars three stories; rooms and walkways have been ingeniously built on different levels like an indoor tree house–some rooms are reachable only by ladder. A horse stall hosts the kitchen, which overlooks an area below where pigs once lived; a swing hangs from a beam near a piano; and books, rugs, plants, and keepsakes fill, but don’t clutter, the enormous space. Burnes’ mother, Carol, a poet, storyteller, and performer, still lives here. “She never throws anything away!” says Burnes.

Down a serpentine driveway in Weston, after pavement gives way to gravel, Jamie Burnes’ unconventional home and studio appear. “It’s our own little vortex,” says Burnes, who still lives in the barn that was transformed into a home in the early 1970s by his father. With grey weathered siding and trapezoidal windows, it has a funky bohemian feel that is eclectic and welcoming. Burnes’ dog, Mosey, wags his tail when we enter the house, where evidence of a creative lifestyle abounds. The post and beam volume soars three stories; rooms and walkways have been ingeniously built on different levels like an indoor tree house–some rooms are reachable only by ladder. A horse stall hosts the kitchen, which overlooks an area below where pigs once lived; a swing hangs from a beam near a piano; and books, rugs, plants, and keepsakes fill, but don’t clutter, the enormous space. Burnes’ mother, Carol, a poet, storyteller, and performer, still lives here. “She never throws anything away!” says Burnes.

Nearby, in his studio, Burnes is creating a small horse out of steel and recycled mahogany. Using photographs of horses for reference, he begins with several pieces of wood that form a rough armature. Next, he cuts out cardboard shapes that he bends and manipulates to form the various surfaces of the horse. When he is happy with the scale and shapes of these mock-ups, he transfers the patterns onto thin pieces of wood, which are his templates for cutting the steel. Using the plasma cutter, “the most awesome tool I have,” he cuts the flat shapes out of steel. Then he hammers them into curved sections that, when welded together, become the flanks, loins, hocks, withers, and hooves. After more grinding to smooth the surfaces and applying a patina, the piece will be finished.

What’s the trickiest part? “Bringing it to life,” Burnes says. “The challenge is finding balance and proportion – on a horse, the head is the same length as the neck, the hip, and the hock. It has to have visual balance and structural balance or else it is ultimately just a hunk of metal and wood.”

What’s the trickiest part? “Bringing it to life,” Burnes says. “The challenge is finding balance and proportion – on a horse, the head is the same length as the neck, the hip, and the hock. It has to have visual balance and structural balance or else it is ultimately just a hunk of metal and wood.”

Dressed in a grungy T-shirt and battered work pants, Burnes moves fluidly between the plasma cutter, the welding torch, and a grinder. It’s noisy business; he wears a pair of earplugs.

Beside the entrance to the studio stands a commissioned sculpture that Burnes has been working on for several months. It is a series of locust wood trunks joined together in a nautilus-like spiral nearly 12 feet high. “This one has been an engineering challenge,” he says. Each of the 107 chunks of locust wood has a rod of steel running through it and both ends are capped with COR-TEN steel. Strung like a tapered necklace, the enormous “beads” of tree trunks defy gravity and reason as they stand in their vertical loops.

As a kid, Burnes says he built go-carts and sandcastles, “the usual sorts of stuff.” In middle school at the Park School, he got a job with Adio Dibiccari – a bronze sculptor – who asked him to copy a bust out of clay and cast it into plaster. “In seventh grade, art was the only class I paid attention to,” he says.

As a kid, Burnes says he built go-carts and sandcastles, “the usual sorts of stuff.” In middle school at the Park School, he got a job with Adio Dibiccari – a bronze sculptor – who asked him to copy a bust out of clay and cast it into plaster. “In seventh grade, art was the only class I paid attention to,” he says.

He attended The Middlesex School, “where they have an incredible art and welding studio,” and where he made sculptures of a dinoflagellate, a microorganism that causes red tide, which he observed under a microscope in biology class.

“I didn’t want to go to art school for college. I was good at engineering, physics, and math. I definitely did not intend to be a sculpture major,” Burnes laughs. Of course, he did major in sculpture, at Skidmore College, virtually living in the sculpture building and becoming the Teaching Assistant for welding classes. Burnes made his first full scale cow in 1997, during his senior year in college, followed by a barnyard of other animals. When his father died in 2000, he started making bears, in honor of him.

After graduation, Burnes says he “got lucky” when he visited his sister in Santa Fe. He took several sculptures to Shidoni Arts, a foundry and sculpture gallery, and landed some important sales, including the sale of an elk to actor Gene Hackman. In recent years, he has been working from a winter studio in Santa Fe, while spending summers in Weston.

Looking ahead, Burnes is interested in doing more large-scale commissions for public spaces. And he has put aside a few tree trunks that he envisions will make the perfect “innards” for a mare and her colt.