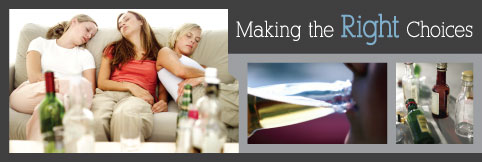

Making the Right Choices

Professionals urge parents to empower kids to handle tough decisions about alcohol use

Professionals urge parents to empower kids to handle tough decisions about alcohol use

Betsy Lawson writer

For teenagers, making a bad decision about alcohol use can cause irreparable harm in a way that few other wrong decisions can. The disciplinary actions school administrators, police officers, coaches, and therapists take in response to alcohol infractions can be swift and severe to be sure, but they all contend that it’s parents who wield the most authority—and obligation—to talk frankly with their teens about the dangers of alcohol, set clear limits, and follow through on the consequences when those rules are breached.

The parent volunteers who run the annual Wellesley Cotillion held in December take this admonition seriously. A list of strict guidelines is mailed out for parents to read and discuss with their teenagers in advance of the event. Notice is made that all handbags and jackets are subject to inspection, and backpacks and large bags are simply not permitted.

The parent volunteers who run the annual Wellesley Cotillion held in December take this admonition seriously. A list of strict guidelines is mailed out for parents to read and discuss with their teenagers in advance of the event. Notice is made that all handbags and jackets are subject to inspection, and backpacks and large bags are simply not permitted.

Further, parents of any guest suspected of being under the influence of a controlled substance, or who behaves inappropriately, will be called to pick up their child immediately. To ensure this policy is carried out, all parents are required to provide a phone number where they can be reached on the night of the Cotillion.

The “zero tolerance” policy seems to be working, says Wellesley parent Donna Fessler who helped run last year’s Cotillion. Granted it was a lot of work for the parents involved, she said, but the event was both a joy and a success.

“The Cotillion is a gift parents are able to give their children,” Fessler said, and the emphasis should be on the positive. “It’s about dressing up, being with your friends, and having a good time,” she said, adding, “and most kids are good kids.”

Nonetheless, Fessler believes adults need to be mindful that teens will test whatever limits are set. “It’s our job to set strict and clear guidelines—and to be sure they’re enforced,” she says, albeit with a delicate touch.

When teenagers know their behavior is being watched and that there will be consequences for breaking the rules, they’re much more likely to make the right choices, says Dr. Robert Evans, director of Human Relations Service (HRS), a private, non-profit mental health agency serving Wellesley, Weston, and Wayland. HRS offers a full range of outpatient diagnosis, treatment, and crisis intervention, including an Adolescent Substance Abuse Program (ASAP). The emphasis of ASAP is to provide swift, practical intervention to the family of a teenager who may be involved in problematic addictive habits.

“Kids who generally are best able to monitor themselves, come from authoritative homes,” Evans says. He defines authoritative as “friendly, but firm; supportive, but not enabling.” In an authoritative home, for instance, a small child has the right to choose whether to eat, but not what to eat. In contrast, Evans says that in an indulgent home, when a child refuses to eat the meal that’s served, the parent prepares a different meal.

“Going hungry briefly—although this rarely happens—isn’t going to hurt the child; constantly getting one’s own way will,” Evans says. What may seem like a minor issue when children are young, however, sets the tone for how they’ll respond to parental authority in the teenage years ahead.

An even more extreme example is the child who protests that he doesn’t want to go to Grandma’s—and the family doesn’t go. That’s an adult decision, Evans says, not a child’s. But increasingly, the line that differentiates adults from children is becoming blurred.

“For a child of the ’50s, seeing a commercial for Viagra during a Red Sox game would have been unthinkable,” he said. “There was a clear notion that teenagers where not ‘mini adults.’ There were still forbidden fruits.”

Now many teens feel entitled to the adult world, including alcohol. Teenagers may argue that since parents drink at parties, they can too. But that’s faulty logic—and it’s against the law, says Youth Safety Officer Brian Spencer of the Wellesley Police Department. Of his 21 years in law enforcement, the past eight have been here in Wellesley. He now serves as the School Resource Officer and runs a variety of programs for different grade levels that cover such topics as cyber-bullying, internet safety, and alcohol awareness.

“It’s all about making smart decisions and keeping the lines of communication open,” he says. For all his time in the classroom, however, Spencer says his influence pales in comparison to the role of the parent.

“It’s all about making smart decisions and keeping the lines of communication open,” he says. For all his time in the classroom, however, Spencer says his influence pales in comparison to the role of the parent.

“Parents need to keep the conversation going, and to listen [to their kids],” Spencer says. The only time not to discuss alcohol use, however, is when a teen’s been drinking. “Make sure they’re safe and that they don’t need medical attention,” Spencer says. But wait until the next day to discuss it and, more importantly, to enforce the consequences that have been discussed ahead of time.

“The parents’ role is not to be their kid’s best friend,” Spencer says. Parents need to lay down clear rules and then follow through when they’re broken. This means talking specifics with their teens about what to do if alcohol appears at a party or if the person driving has been drinking. Role-playing can help.

Spencer believes that it’s okay for teens to make their parent the excuse for not drinking by saying, “my parents are up when I get home, so I can’t drink.” Of course, this means parents must actually be awake and be checking teens’ breath when they do come home. “If they know they won’t get away with it, they’re less likely to take that chance.”

School administrators and coaches know this. In 2007 they worked with the Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association (MIAA) to heighten penalties for student-athletes caught drinking, using drugs, smoking, or chewing tobacco. Prior to the rule change, if a player was caught in the off-season, there was essentially no penalty. Those caught now (even in the summer) will lose eligibility the next time they play a sport. In short, there’s never a time when coaches can look the other way when it comes to underage drinking. MIAA officials do encourage athletes found in violation to continue practice, however, because they don’t want them out there with nothing to do, taking chances.

But take chances they will, the experts say. A feeling of immortality is part of adolescence. Adults need to be the ones who constantly remind teens about safety and about consequences.

That’s why before the Cotillion each year, Wellesley’s Youth Commission hosts a public Alcohol and Youth Awareness Forum together with the Wellesley Police. Maura Renzella, the commission’s youth director, says that during the forum a documentary film about a hit-and-run accident involving a drunk driver is shown, followed by a question and answer period.

Renzella, who also co-leads the “Thinking about Drinking Basics” with Officer Spencer for eighth graders, says that kids who’ve had conversations with their parents beforehand and know that they can call and be picked up with no questions asked, are more likely to call their parents when the time comes.

“With today’s technology, you’d be surprised how quickly you can go from texting ‘Mom and Dad are at the movies’ to having 50 kids knocking on your door looking for a party,” Renzella said.

“In Wellesley and Weston, the houses are big and the basements can be cavernous,” Renzella says. Teens have become savvy enough to keep both the number of friends and the volume of music down, in hopes that the adults upstairs—when there are some—won’t intrude. “But you have to intrude,” she said, all while trying not to embarrass your teen too much.

But many parents grapple with how to exert their authority, while still allowing their teens to assume more responsibility for their own behavior, says Dr. Dale Sokoloff of Wellesley-based DKS Consulting Group. Sokoloff, a clinical psychologist and former founding member of the Eating Disorders Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, is a pioneer of Empowerment Fitness® (see sidebar).

Her group offers workshops to help parents empower their children to face difficult decisions. “No parent can envision every scenario his or her child is going to face,” Sokoloff said, so the emphasis needs to be on the process of how good decisions are made.

“By eighth grade, kids who want access to alcohol are beginning to get it. They’re very savvy,” Sokoloff said—be it through an older sibling or classmate or an unlocked liquor cabinet. “So rather than always talking about what they shouldn’t do, focus instead on what they should do,” she adds. Frame the conversation in terms of identifying what they really want. Some good questions: What kids have you chosen to be with? Will what you’re doing be a good experience or bad experience?

And this is a conversation to be having with children of all ages, Sokoloff says. Gear the content toward their current experience such as the rule about wearing a helmet when biking or skateboarding. Questions can help kids connect actions with consequences: Do you know why wearing a helmet is important? How would you say ‘no’ to a friend who made the suggestion not to? Here’s what will happen if you’re caught without your helmet.

“Parents are so much more important to their kids than they realize. [Kids] may look like they’re rejecting you, but bottom line, the most important people in their lives are their parents,” she says.

And even when you think they’re not listening, they are—especially when it comes to the high-charged temptations involved in drinking, smoking, sex, and driving. These are conversations that can be easier to have side-by-side in conjunction with another activity, Sokoloff says. Repetitive physical actions like throwing a baseball, playing ping-pong, or shooting baskets can establish a natural rhythm for conversation, even for the most taciturn teen.

“It doesn’t have to feel like a lecture,” Sokoloff says, which teens are likely to tune out.

Karen Hoffman, Sokoloff’s partner at DKS Consulting, added, “kids are going to make mistakes. Not to panic.” The important thing is that they learn to pick themselves up so that mistakes become learning opportunities, something they refer to as “failing forward.”

Parents are sometimes so afraid of their kids being unhappy or having to face unpleasant consequences as a result of their actions, that parents try to keep them from failing, often to the extreme. “When the coach calls you and says ‘your kid is off the team [for drinking],’ Hoffman says, “instead of arguing your case, say ‘thank you.’”