The Flags of Our Wellesley and Weston Fathers

Beth Hinchliffe writer

Patrick Collins photographer

For sixty years, they have been our quiet neighbors.

For sixty years, they have been our quiet neighbors.

When their country was threatened in the early 1940s, these young men interrupted their schooling, their marriages, their careers, and their lives to enlist and serve in the Second World War. For the sake of future generations, they sacrificed their youth alongside friends who sacrificed their lives. At the end of the war, returning forever changed by the scars of battle, our veterans chose to come to Wellesley and Weston to create their homes, raise their families, and devote themselves to their towns.

Current residents might not realize that the man elected to Wellesley Town Meeting for 50 years was the boy who won a Bronze Star for risking his life to save his men in a German field. Or that the longtime next door neighbor in Weston received a Purple Heart when his plane was shot over Japan. Or that the favorite Wellesley policeman once had to steer his landing craft amid hundreds of bodies during the invasion of Guam.

These are the boys who secured our future; the men who shaped our towns. In their 80s and 90s now, their ranks have diminished to a few dozen, where once they totaled nearly 4,000. Though they are physically weaker, they are still immensely strong in their courage and their example. When interviewed for this article, every single one said: “I’m not a hero. I did what I had to do for my country. The real heroes are the ones who didn’t come home.”

Meet some of Wellesley and Weston’s “Greatest Generation.”

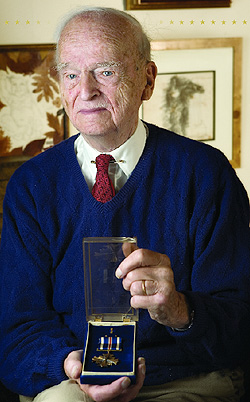

Bob Hinchliffe, now 84, was a Boston University ROTC Cadet when he enlisted in the Army shortly after Pearl Harbor and entered active duty at the end of his junior year. As a 20-year-old lieutenant with the 78th Infantry Division, he engaged in combat throughout Europe, including in the Hurtgen Forest in Germany (where he earned the Bronze Star), the Battle of the Bulge, and the Bridge at Remagan. At the end of the war, he was selected to be the Aide to the Commanding General of Troops in Berlin, where he served with the Army of Occupation. After discharge, he returned to Boston University (where he was later named to the Alumni Hall of Fame) and studied to become a certified public accountant. He moved to Wellesley after marrying (the late) Dorothy, where they raised their daughter, and where he still lives with his second wife, Jeanne. In addition to being a Town Meeting member for 50 years, Hinchliffe also served on a number of committees. He was elected president of Rotary and the Central Council PTA, and served as a board member of the Community Center and Country Club. He has also worked as a volunteer for the Council on Aging and St. Paul Church. He received Wellesley’s Veterans’ Service Award (he rode at the head of the 2006 parade), the Distinguished Service Award, and witnessed the establishment of the Robert J. Hinchliffe Military History Collection at the Wellesley Free Library.

From the moment we crossed from England to France until the war ended for us in Wuppertal, Germany, we were in battle every day. We made our way across Europe capturing town by town. Every day was the same, yet no two days were alike.

From the moment we crossed from England to France until the war ended for us in Wuppertal, Germany, we were in battle every day. We made our way across Europe capturing town by town. Every day was the same, yet no two days were alike.

Almost every night we slept in a different place. We’d either dig our own foxholes in the frozen earth, or take shelter in an unheated bombed-out building. We carried our K-rations with us, and for warmth we only had a blanket and the clothes on our backs; the same clothes we’d worn for weeks or months at a time. We tried to find time to catch some sleep, and even then we slept with our helmets and overcoats on. We were constantly under fire.

In early December 1944, we were in the battle for the village of Rollesbroich, Germany, in the Hurtgen Forest. Some of our men lay injured in the mined field, unable to make it back, easy targets for the Germans. I got some of my men to volunteer to come out with me to bring them to safety. It was snowing. We had to carry one at a time, on our backs, under fire, for about a half-mile. It seemed like an eternity. I’d made a few trips and had gone back for another when a barrage of German artillery shells found us. Three of my men next to me were killed. We were honored with the Bronze Star.

I’m telling my story not for myself, but in memory of all those young men who fought alongside me, but who weren’t as blessed as I was to make it home. They’re the heroes. They’re the ones we should remember and honor, and keep in our prayers, forever. George Amadon, now 90, was newly married when he enlisted in the Army Air Corps shortly after Pearl Harbor. A technical sergeant, he became a command gunner on an 11-man B29 bomber, receiving a Distinguished Flying Cross and Purple Heart for 30 missions over Japan from their base in Saipan. After his discharge late in 1945, he and his wife Elizabeth (who died after their 53rd anniversary) bought an historic home in Weston, where they raised five children. Known as “Mr. Veteran,” he still lives in town with his second wife, Meredith. A longtime organizer of the Memorial Day observances, he has also been an Historic District commissioner, the Graves Officer, a board member of the Weston Historical Society, and volunteers to speak in schools about his war experiences.

We flew missions in our plane (“the Little Gem”) over every major city in Japan, dropping forty 500-pound bombs each time. It took us eight hours of flying to get there.

We flew missions in our plane (“the Little Gem”) over every major city in Japan, dropping forty 500-pound bombs each time. It took us eight hours of flying to get there.

We were hit five times. Sometimes we’d have to fill the holes with blankets to keep the pressure in. Once the plane flying with us was hit. We saw his engine on fire, and the tail gunner, my buddy who lived in our hut, waved at us. They never made it back.

On January 29, 1945, we were over Tokyo when the Japanese caught us in their searchlights. It was so bright that if I’d had the Lord’s Prayer on a pin, I could have read it in the light. I don’t remember what happened next. My blister (glass bubble) took a direct hit. The flak went through my leather and metal helmets and knocked me out. When the glass blew out, at 26,000 feet, I lost my pressurized compartment and everything flew out — the helmet, my oxygen mask. The other gunners managed to drag me out of my seat, found extra oxygen, and saved my life. I came to on the flight home, with a big welt where I’d been hit, and permanent hearing loss in my left ear.

We flew 30 missions. I was discharged late in 1945. That was over 60 years ago, and I still have nightmares about it, think too much about it. Every Memorial Day, I help put flags on the graves of every veteran in town. I’ll never forget the war, and I’ll never forget them.

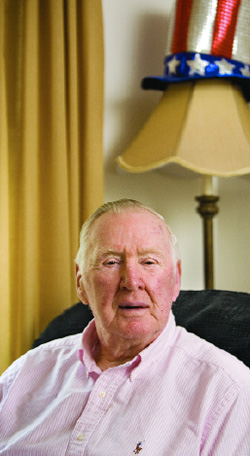

In 1942, John “Sparky” Tracey, now 89, enlisted in the Coast Guard, which during the war was assigned to the Navy. He served in the Pacific on the 105-foot tender Tupelo, in the task force of Admiral Nimitz, for the invasions of the Marianas, Guam, and Saipan. After the end of the war, he returned home, married Wellesley native Mary Sullivan (who died in 2002), became the Wellesley Police Department’s Safety Officer, and raised six children in town. Active in the Wellesley Boy Scouts, at St. Paul Church, with the American Legion, and still volunteering with the retired nuns at Elizabeth Seton, he has been a parade Grand Marshal, and received the Wellesley Award for service to his community.

In 1942, John “Sparky” Tracey, now 89, enlisted in the Coast Guard, which during the war was assigned to the Navy. He served in the Pacific on the 105-foot tender Tupelo, in the task force of Admiral Nimitz, for the invasions of the Marianas, Guam, and Saipan. After the end of the war, he returned home, married Wellesley native Mary Sullivan (who died in 2002), became the Wellesley Police Department’s Safety Officer, and raised six children in town. Active in the Wellesley Boy Scouts, at St. Paul Church, with the American Legion, and still volunteering with the retired nuns at Elizabeth Seton, he has been a parade Grand Marshal, and received the Wellesley Award for service to his community.

It was very hot and muggy on the ocean, and our bodies developed fungus. I had a middle berth, sleeping right over the ammunition. Once we had to transport 100 tons of dynamite, and I was skeptical about sleeping on top of that, especially when the sonar picked up submarines. But if it happens, it happens.

The most harrowing time was at the invasion of Guam. I had to steer the landing craft into the harbor. We maneuvered through all the bodies of Japanese soldiers who had just been killed. They were floating face up. Hundreds of them, everywhere. I was a kid who had never left home, and it really bothered me. Most of them were only kids like me. It stayed with me. I never forgot it.

I just did the right thing, serving my country. When my son, David, signed up to go to Vietnam, I didn’t know if I would ever see him again, but I was so proud. So proud. I met another father who said he sent his son to Canada to avoid the draft. That bothered me. Still does. The freedom we have is worth our sacrifice. People have to realize we have so many things to be thankful for; how great it is to live in this wonderful country.

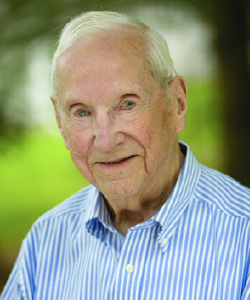

The day after Pearl Harbor, Weston native Harry Jones, now 94, joined the Navy. He was assigned as a petty officer on the USS Eugene E. Elmore, a destroyer escort, which served in both the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets, first protecting supply convoys of up to 100 ships, then later searching for and destroying submarines. His naval service was completed in 1945. In 1957, he married Jean, another Weston native, and they raised their son in town while Harry worked as Controller at Wellesley College and as Weston’s Town Accountant. He was elected Town Clerk for 18 years, and has been President of the Weston High Alumni Association and the Weston Men’s Club, Chair of the War Memorial Scholarship, Commander of the Weston American Legion, Treasurer of the Weston Historical Society, and a longtime member of the Weston Methodist Church.

We were in a Hunter-Killer Group with the aircraft carrier the USS Block Island, locating and destroying U-boats in the shipping lanes off North Africa. On May 29, 1944, a U-boat fired a torpedo and hit the Block Island. Then two more hit. More than 1,000 men were thrashing in the oil-soaked water. While other ships took survivors aboard, we searched for the U-boat, and our sonar located it when it ascended to periscope level to see the damage. We fired once, then twice more. We knew our missiles had found it when we saw debris and oil come to the surface. I felt so badly. We were just a crew doing our job, and there had been 75 young Germans onboard just doing their jobs. They were somebody’s children, too. Then we saw the Block Island’s bow go straight up in the air, and it just went under. The only aircraft carrier lost in the Atlantic. It had been our great big mother. Now we were alone on that enormous ocean.

We were in a Hunter-Killer Group with the aircraft carrier the USS Block Island, locating and destroying U-boats in the shipping lanes off North Africa. On May 29, 1944, a U-boat fired a torpedo and hit the Block Island. Then two more hit. More than 1,000 men were thrashing in the oil-soaked water. While other ships took survivors aboard, we searched for the U-boat, and our sonar located it when it ascended to periscope level to see the damage. We fired once, then twice more. We knew our missiles had found it when we saw debris and oil come to the surface. I felt so badly. We were just a crew doing our job, and there had been 75 young Germans onboard just doing their jobs. They were somebody’s children, too. Then we saw the Block Island’s bow go straight up in the air, and it just went under. The only aircraft carrier lost in the Atlantic. It had been our great big mother. Now we were alone on that enormous ocean.

In my four years, we were strafed by Luftwaffe, bombarded with skip bombs, targeted by Kamakazes, and almost sunk by a typhoon, but the most terrifying moment of all was watching the Block Island silently slip under the surface.

The whole war was a big team effort, both in the service and at home. We all had to pull together. There would never have been victory if it hadn’t been for the sacrifices and support of the American people, rationing and working and being behind us a hundred percent. It was a different time, a different war, a different nation.

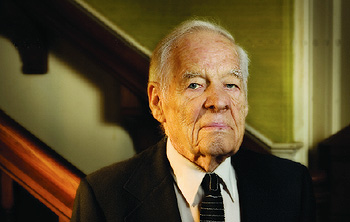

Dr. Bob McGuane, now 95, had just set up his dental practice in Wellesley when he heard the news about Pearl Harbor and immediately enlisted in the Navy. Lieutenant, then Commander, McGuane was assigned to the battleship the USS Texas, which saw action in the Atlantic and North Africa. When he was discharged in 1946, five years after enlisting, he and his wife Marcella bought the landmark gray house on Worcester Street that was both his home and dental practice, where they raised their two children and a parade of Newfoundland dogs, and where they still live today.

Dr. Bob McGuane, now 95, had just set up his dental practice in Wellesley when he heard the news about Pearl Harbor and immediately enlisted in the Navy. Lieutenant, then Commander, McGuane was assigned to the battleship the USS Texas, which saw action in the Atlantic and North Africa. When he was discharged in 1946, five years after enlisting, he and his wife Marcella bought the landmark gray house on Worcester Street that was both his home and dental practice, where they raised their two children and a parade of Newfoundland dogs, and where they still live today.

We crossed the Atlantic many times, and it was always brutal. I couldn’t believe the way the ocean could transform itself into a real inferno. The storms were spectacular, terrifying. We’d take water right over the top. The bow would go straight down and you’d wonder if it would ever come back up.

We were at Port-Lyautey, Morocco for the invasion of Africa, and in the invasion of Italy. We never lost a man. The Texas was hit by a shell during the Normandy invasion, but it didn’t go off.

I was the dentist for 1500 men. It was a luxury to come back to Wellesley and have an office that didn’t pitch back and forth. I also had to do a lot of surgery for injuries. I developed a fracture stabilizer for a pilot whose facial bones were shattered in a crash. I had to improvise — I cut up a chair to use the padding, I boiled plexiglass and shaped it. And it worked.

I was the dentist for 1500 men. It was a luxury to come back to Wellesley and have an office that didn’t pitch back and forth. I also had to do a lot of surgery for injuries. I developed a fracture stabilizer for a pilot whose facial bones were shattered in a crash. I had to improvise — I cut up a chair to use the padding, I boiled plexiglass and shaped it. And it worked.

I never questioned giving up five years of my life. We never thought it was a sacrifice, we were doing what everyone was doing. We were fighting because we were attacked. We were doing our duty. We were protecting our country.

recent comments