The Greatest Wellesley Sports Star You Probably Never Heard Of

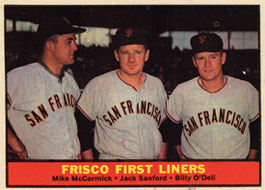

Jack Sanford’s baseball career would seem to be the stuff of legend: the feisty fire-baller toiled for seven years in the minors, pitched his way to National League Rookie of the Year at the ripe age of 28, and nearly led Willie Mays and the San Francisco Giants over the New York Yankees in Game Seven of the World Series 50 years ago this fall.

Yet in Wellesley, where the ballplayer was born John Stanley Sanford on May 18, 1929 and pitched for the high school team in the mid-1940s, his name is hardly a household one these many years later.

these many years later.

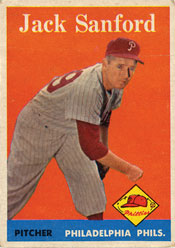

Things might have turned out quite differently had Sanford, who died at the age of 70 in West Virginia in 2000, been snapped up by the Boston Red Sox or Boston Braves following a tryout at Fenway Park in 1947. As a young man, Sanford worked as a driver for Braves millionaire owner Lou Perini, Sr., and his high school baseball coach Hal Goodnough was a part-time Braves scout. You would think that would have given Sanford an in with one of the local teams, but they both passed on him. Instead, the Philadelphia Phillies wound up signing young “Johnny” Sanford for $125 a month and launched him on a 12-year major league career during which he would compile a 139-101 win-loss record, and later coach and scout for major league teams.

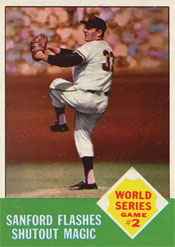

Sanford’s legacy also might have been very different in Wellesley today if the Giants had topped the Yankees, instead of losing that deciding Game Seven on a soggy Candlestick Park field back in October 1962. The remnants of Typhoon Freda wreaked havoc on that Series, causing a four-day delay between games five and seven. But it gave Sanford a third chance to start in the Series vs. a Yankees line-up stacked with big name hitters such as Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris. Sanford, the National League’s runner-up for best pitcher with a 24-7 record that included 16 straight victories, dazzled the Yankees in winning Game Two by a score of 2-0 and lost Game Five by a 5-3 margin despite striking out 10. In Game Seven, Sanford surrendered just one run on a double-play, but Yankees second baseman Bobby Richardson snared a line drive off the bat of slugger Willie McCovey with two outs in the bottom of the 9th that would have given the Giants the championship if it had been hit about two feet higher. Baseball scribes have called the 1-0 game one of the best pitching duels in World Series history. But alas, opposing pitcher Ralph Terry won the Series Most Valuable Player Award, an honor that no doubt would have been Sanford’s had the Giants pulled out the victory. “I never pitched better in my life,” Sanford said after the game.

Hometown Hero

Hometown Hero

The right-hander’s pitching accomplishments weren’t overlooked at the time by his hometown.

Selectmen designated February 7, 1963 as “Jack Sanford Day in Wellesley,” which entailed visits to schools, a luncheon with the Kiwanis Club, and a banquet featuring roast rump of beef at Babson College’s Knight Auditorium that was attended by some 500 townspeople and sports celebrities, including then Boston Red Sox manager Johnny Pesky.

A testimonial trumpeted the solid six-foot, 190 pounder’s achievements, reading in part: “[He] has set a living example not only for the youth of Wellesley, but for the entire nation – an example of a young man who never gave up, and by clean living, hard work, sacrifice, and desire, reached the top… Overall he’s just a grand guy, and that’s why we’re here this evening.” Wellesley High School also agreed to honor the team’s best pitcher annually with the Jack Sanford Award, which has been phased out over time.

Sanford was the youngest of four children, raised by a father who worked for the town of Wellesley and a mother with Irish roots who often worked outside the home to help support the family. The Sanfords started out in Wellesley Hills on Oakland Circle, but reportedly moved to what was considered a drier part of town in what’s now the Cleveland Road area after young John came down with pneumonia and a tonsil infection. On a more positive note, Sanford also caught the baseball bug and played whenever he could.

Sanford was a good, though not great, high school pitcher until he became a senior and “really came to life,” said Jim Decker, a 1946 Wellesley High grad who played baseball and football. Sanford finished his high school pitching career in style, tossing a no hitter vs. Needham High on June 6, 1947.

football. Sanford finished his high school pitching career in style, tossing a no hitter vs. Needham High on June 6, 1947.

Still, it took a while for Sanford to impress a wider audience.

Joe Morgan, the ex-Red Sox manager best known for the “Morgan Magic” winning streak he led the team to in 1988, said he didn’t think much of Sanford as a pitcher when the two squared off during Morgan’s days at Walpole High School. In the mid-1950s, though, Morgan’s army team from Oklahoma visited Sanford’s army team at Fort Bliss in Texas for a tourney. “I told our guys that we wouldn’t have any problem with Sanford when I heard he was pitching,” Morgan said. “He shut us out 5-0 on two hits. He got a lot better.”

That pitching ability also kept Sanford out of the Korean War, according to his son John, a golf course designer in Florida. “There was a general who wanted him for the army team,” according to the younger Sanford.

His pitching exploits for the army followed a longer-than-average minor league career marked by pitching and emotional control issues. Despite winning 14 or more games four times in the minors, Sanford’s long road to the majors included stops in towns and cities by names of Bradford, Dover, Americus, Wilmington, Schenectady, Baltimore, and Syracuse. “I had to creep up the hard way,” Sanford is quoted as saying in The Giants Encyclopedia. “They say if you can’t make the majors in five years you’d better quit. I almost did.”

Once Sanford made it to the majors, for a mediocre Phillies team, he put everything he had into his pitching. “I have to put every ounce of strength into every fastball I throw, or I get blasted,” he told one magazine writer in 1963. “I can’t pace myself.”

Once Sanford made it to the majors, for a mediocre Phillies team, he put everything he had into his pitching. “I have to put every ounce of strength into every fastball I throw, or I get blasted,” he told one magazine writer in 1963. “I can’t pace myself.”

Sanford, who developed a curveball and slider to go along with his fastball, earned Rookie of the Year honors in 1957 with a 19-8 record and a league-leading 188 strikeouts. His efforts reportedly more than doubled his salary to about $16,000 the next season, although like most ball players back then, he also took side jobs, including one as a salesman for a corrugated box maker.

A Saturday Evening Post profile of the 1947 National League All-Star pitcher that following spring bore the headline “Baseball’s Oldest Youngster.” It described Sanford as frank, hyper-competitive, and alternately friendly and hard to deal with.

His major league teammates to this day attest to Sanford’s determination.

“We didn’t have radar guns back then, so we didn’t know what his top velocity was, but it was fast,” said Jim Davenport, an infielder for the Giants on that 1962 World Series team. “He was a great competitor and we all enjoyed playing behind him.”

It sure beat facing him.

“He stood on the mound like he owned it,” said WHS teammate Decker, who went to see Sanford pitch professionally when he came to the west coast to play for the Giants and later the Angels. “He brushed batters back like crazy.”

Decker claims Sanford could have made the majors as an outfielder if his pitching arm didn’t take him there, and in fact Sanford went 3 for 7 at the plate during the World Series. Sanford was an excellent all-around athlete, and golf became his passion off the ball field, with Giants manager Alvin Dark giving him his first clubs. Sanford also enjoyed hunting in his spare time.

“Smiling Jack”

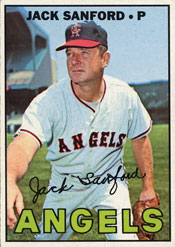

A darker side of Sanford’s personality also grabbed headlines during and after his baseball career, which wound down with the California Angels and Kansas City Athletics following arm and shoulder troubles.

After Sanford’s World Series appearance, a 1963 Sport magazine article titled “Jack Sanford’s Grim World” laid bare the pitcher’s on- and off-the-field demeanor, all the while acknowledging his pitching skills. The author wrote that “Jack Sanford is a man of many moods, mostly bad” and that “Smiling Jack Sanford is a blue-eyed blond, somewhat less adorable than Shirley Temple. His blue eyes are hard and cold, shielded by heavy brows, and he squints around them… His jaw is hinged, his face flexible, and he twists it into various expressions, most of them forbidding, defiant, scowling. He saves his smiles for his friends, and he doesn’t make friends easily.”

Another report, in a golf book, described Sanford as bloodying his own head from whacking himself with golf clubs after particularly bad shots.

Sanford’s son John acknowledged that his dad was known for his explosive temper: “He always said that’s what helped an average kid from Wellesley to make it in the bigs. He carried it over to the golf course, where it wasn’t beneficial, but we didn’t see much of it at home.” Sanford’s daughter Laura added: “As to my dad’s so-called temper, he demanded so much from himself and was frustrated when he failed. Less than a perfect performance on his part was not sufficient; he was very competitive.”

Sanford’s son John acknowledged that his dad was known for his explosive temper: “He always said that’s what helped an average kid from Wellesley to make it in the bigs. He carried it over to the golf course, where it wasn’t beneficial, but we didn’t see much of it at home.” Sanford’s daughter Laura added: “As to my dad’s so-called temper, he demanded so much from himself and was frustrated when he failed. Less than a perfect performance on his part was not sufficient; he was very competitive.”

Sanford, who married Wellesley High sweetheart Patricia Reynolds while on military leave in 1955, raised four children in Duxbury and in other communities nearby where he played, from the east to west coasts. Decker said that while Sanford reaped acclaim for his baseball prowess during his playing days, it was the ballplayer’s wife who held the family together and “is really the one deserving of the accolades.”

Though in the end, Sanford the pitcher also has gone largely underappreciated, said Richard Johnson, a longtime Giants baseball fan and curator for the New England Sports Museum, which does not feature any Sanford memorabilia.

“He has been forgotten about even by Giants fans even though for at least one season he was the best pitcher on a very good pitching staff,” Johnson says. “Imagine how much a pitcher today with his skills, if developed properly, would be appreciated.”

recent comments