If Stones Could Speak…Part 2

Peter Golden writer

Peter baker and Peter Golden photographers

The story you are about to read is odd and entirely foreign to the Wellesley we know today. Frankly, it is fraught with conflict, tragedy, and loss. But for all its amazing twists and turns, it is our story. There is ample evidence that it all happened here, even three centuries and more after the fact. And it is not without consequences.

The story you are about to read is odd and entirely foreign to the Wellesley we know today. Frankly, it is fraught with conflict, tragedy, and loss. But for all its amazing twists and turns, it is our story. There is ample evidence that it all happened here, even three centuries and more after the fact. And it is not without consequences.

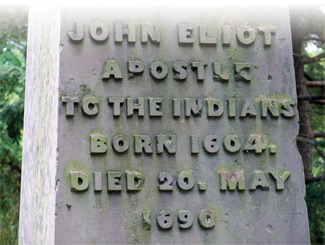

A Visionary Cleric

In the mid-1600s, the Puritan missionary John Eliot and a small band of his Native American followers founded a “Christian Commonwealth” on the banks of the Charles River in what is now present-day Wellesley and Natick. Eliot was what religious scholars call a “sequential millenarian,” a visionary cleric whose every day was devoted to promoting the Second Coming of Christ.

Like all his brethren in the Puritan faith and especially those admitted to its ministry, Eliot considered himself among those predestined for salvation. This he knew through a rigorous course of study, contemplation, prayer, and public testimony. Those were just a few of the many steps that led to full membership in the Puritan church, a sect that viewed itself as the only true faith to emerge from the religious conflicts surrounding the English throne in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

There were other elements of the Puritan persona that did not bode well for the native tribes inhabiting the region west of Boston. Custom, law, strict adherence to Church of England morality, and obligation to the Crown prior to coming to the New World created a mentality obsessed with social control as well as faith. But how might that apply to natives?

What exactly did bring Eliot to what at first was called “The Dedham Grant” in 1651, and then further westward in subsequent years to found over twenty “Praying Indian Towns”? And what led to the demise of those towns and the scattering of their inhabitants to the four winds, some to the Caribbean and even the West coast of Africa?

The Eliot Church in South Natick.

With assistance from Native American helpers, Eliot created an Algonquian alphabet out of thin air, a dictionary, and then, over the course of a decade, full translations of the Old and New Testaments in native dialect. He has been called America’s “first linguist,” and one can see his work in the Wellesley College Library and the Natick Historical Society, which both hold rare second editions of Up Biblum God in their special collections.

The First Utopian

Eliot was also America’s first English-speaking utopian. His Christian Commonwealth served as a kind of charter for the Natick Plantation, the place to which he repaired with his Native American followers at the invitation of a local Nipmuc clan leader named John Speen. But Eliot was not simply trying to save souls; his vision went far beyond that.

Along with some of his Puritan brethren, he sincerely believed that Native Americans, both in these parts and throughout the New World, were descended from the Lost Tribes of Israel. He and his colleague John Cotton found substance for this odd idea in Biblical prophecy and in a long-forgotten book published in London in 1650. Cotton, the dean of the ministry accompanying the Puritans to Boston, advanced a second idea – that upon the joining of New World Indians with Protestant converts in the “Ten Kingdoms” of Europe, a triumphant cohort might then march upon Jerusalem, where on the Plain of Megiddo the Final Judgment would occur and Jesus Christ the Redeemer would return to earth.

All this may sound a bit over the top when applied to a small village composed of “wikiups”, (domed shelters made from bent poles and bark) and a drafty meetinghouse set within a stockade in the “howling wilderness” of Wellesley-Natick. But there is more to this strange tale than that.

Along with their faith and their ostensible desire to evangelize the Indians, the Puritans and their Pilgrim cousins, who earlier had come to Plymouth, brought with them a fiercely entrepreneurial spirit and overwhelming desire to own land.

Freed from Constraints

Freed from the religious and civil constraints of England, the early Puritan pioneers invented different ways to worship and govern themselves in their new land. But culture dies hard. They imposed social norms upon themselves and Native Americans which in many ways were no less obsessive and controlling than those left behind on the other side of the Atlantic.

While Puritan farmers in what we now call MetroWest focused on town building and farming, they did not forget to attend to conjugal duties. Historians have observed they were the most fecund group in the history of the world, regularly churning out families of ten, fifteen, and more. The resulting population pressure – the 20,000 English who participated in the “Great Migration” between 1630 and 1642 grew to over 80,000 by 1675 – and the “land hunger” that preoccupied so many of them created growing tensions between colonials and Native Americans.

History waited only for a spark to provoke a fierce and all-enveloping insurrection in response. Led by Metacom, the youngest son of Massasoit, also known as King Philip, Native Americans in New England went on the warpath with a vengeance. In part, they were provoked by one of Eliot’s followers from Natick.

Native American homesteads surrounded Lake Waban.

John Sassamon was given the task of bringing Philip into the Christian camp. But Philip, last grand sachem of his people, the Pokanoket, part of the Wampanoag, would have none of it. Sassamon played a double game as secretary to Philip and source of intelligence for colonial authorities. When he “woke up dead” one late winter’s morning under the ice of a Plymouth pond, three perpetrators – all henchmen of Philip – were rounded up, tried, and executed in a colonial court. Hostilities soon commenced.

Into the Maelstrom

It was then that the people of Wellesley and Natick, residents of the first and largest of Eliot’s Praying Indian towns, were precipitously yanked out of their roles as Christian redeemers and into the maelstrom swirling between the colonial-Indian divide. With only a day’s notice, and “for their own protection” as well as “reasons of security,” they were evicted by armed guards from their modest homes and marooned on Deer Island in Boston Harbor, along with Indians from other Praying Towns.

All this occurred in the late fall of 1675 and by the following spring half of the estimated five or six hundred left without food or shelter on the windswept island were dead. Meanwhile, the General Court – then as now the chief legislative body in the Commonwealth – struck a bargain with Praying Indian leaders.

Protesting their lack of involvement with Philip and willingness to serve in his pursuit, the Native Americans made individual braves available for intelligence gathering. They also took steps to form a counter insurgency in the form of a small but potent special-forces group under Captain Benjamin Church of Rhode Island.

While the war, the casualties of which remain the highest on a per capita basis in American history, raged on, Boston escaped attack. But Providence, Springfield, Worcester, and Groton were torched, along with upwards of 20 other towns, including nearby Sudbury, where 50 colonials died in the spring of 1676. Whole sections of the colony were depopulated. An estimated 5,000 head of cattle, half the colonial herd, were slain.

Thomas Sawin’s milldam can still be seen in the Broadmoor Wildlife Sanctuary in South Natick.

But by far the human toll was the most devastating: It is estimated as many as two to three thousand colonials died and twice that many Native Americans. Prior to the close of the war in the late summer of 1676, the General Court turned the Natick Plantation into a concentration camp, building a stockade and stone fort on the hill above the west bank of what is now called Lake Waban.

Using Praying Indian towns to the north and west as lockups, captured and surrendered braves were moved to Natick and then brought to Boston for trial and disposition. Summary execution often followed, or “transport” to the Caribbean for sale into slavery.

Eliot protested, still seeking to save souls in the name of the Second Coming to which he had dedicated his life. But the General Court and other towns, where anti-Indian sentiment ran high, overruled him. The colony was a hundred thousand pounds in war debt and selling Indians into slavery was a well-established means of raising funds. It would be a generation before the war’s expense was liquidated.

Meanwhile, Caribbean plantation owners participating in the budding colonial slave trade were wary of rebellious Indians, even at bargain prices. Of the estimated 200 to 300 sent their way from Wellesley and Natick, some remained un-auctioned. Left aboard slave ships, they were dumped on the West Coast of Africa, with a delegation in Tangiers seeking repatriation in later years. History does not tell if they were redeemed.

Final Days of War

More than one historian has noted the pivotal role played by the Praying Indians when colonial authorities finally overcame their initial skepticism. Some have gone so far as to suggest their energy and skill in the field was the deciding factor in Philip’s defeat.

Harried by the colonials and their Praying Indian allies, Philip returned to his ancestral seat at Mt. Hope, where on August 11, 1676, he was shot dead by a Praying Indian. Tactically, the area where he made his last stand was indefensible, which he surely knew.

But it is the date of his death that is more intriguing: August 11 marks the Pleiades meteor shower – that time in Native American spiritual lore when dead souls fly up to Manitou, the Indian deity. Philip may have staged a symbolic suicide.

His wife and son were promptly sold into slavery. Native America in New England, and especially so in Massachusetts—with the exception of Wampanoags on the Cape and Islands and Pequots in Rhode Island who remained neutral—was defeated and virtually destroyed.

There are a few inconvenient details here: the first in the form of public perception in the 19th century, the other in an examination of the cultural aspects of Puritan social policy. In the 1840s Philip began to be seen as a patriot in his own right, defending his land, prerogatives, and people against a foreign, occupying power. This notion was propagated through a series of popular plays that went far toward romanticizing Philip as “the last of his race.”

There are a few inconvenient details here: the first in the form of public perception in the 19th century, the other in an examination of the cultural aspects of Puritan social policy. In the 1840s Philip began to be seen as a patriot in his own right, defending his land, prerogatives, and people against a foreign, occupying power. This notion was propagated through a series of popular plays that went far toward romanticizing Philip as “the last of his race.”

In our own time, historians have noted that the Puritan’s “take-no-prisoners” style of warfare and post-war policy of exile and enslavement became a model for US President Andrew Jackson and the “Trail of Tears” that displaced the Cherokee nation in the South. Later, a similar approach was taken in the Western Territories, where Native Americans found themselves combating phalanxes of Pony Soldiers, battle-hardened veterans of the Civil War, who took less than 30 years to reduce them all to reservations and lay unchallenged claim to the American West.

But let us return to our narrative. There is more to tell here – about how the Praying Indian towns were consolidated into Natick after the war, which effectively became a penal colony. At least one historian has confirmed the existence of General Court laws from the 1670s and ’80s forbidding egress from the Natick Plantation without a pass. To flaunt this rule was to risk instant arrest.

As time went on and contention faded, the older generation of Praying Indians entered more fully into colonial life, even going so far as to invite Thomas Sawin, a Sherborn carpenter, to set up both a saw- and gristmill on Indian Brook at the west end of the Plantation. Younger native women, given the scarcity of eligible Indian males, married black slaves in order to find mates. This, in part, explains the origins of Crispus Attucks, a Natick Praying Indian of part African-American descent, who became the first martyr of the American Revolution.

Slowly, the Natick Plantation began to fade as the Eliot Church lost its congregation (tuberculosis and rheumatoid arthritis, endemic into the later 19th century, ran rampant among Native Americans) and English farmers bought out native land holdings. Many older Indians were too feeble to farm, and without financial resources other than their land with which to sustain their old age, they began to leave town.

Succeeding native generations still played a role in the community. But a split in the Plantation church led to the removal to Natick Center of non-Indian congregants at the end of the 18th century. Finally, the incorporation of Natick as a separate legal entity from West Needham (a successor to Dedham, which claimed Wellesley until 1881), drew a curtain across our past.

Unexpected Ways

Native America endured, if in unexpected ways. Many male members of succeeding generations made their living as professional soldiers and hunters, while others followed those who had fled to French Canada during King Philip’s War. Combatants on both sides in a series of North American conflicts lumped together under the catchall of “The French & Indian Wars” descended from both Praying Indians and Philip’s braves. Throughout this period, native women made brooms and baskets, worked as midwives and domestics, and generally descended beneath the surface of 18th- and 19th- century social life.

Yet even in the midst of catastrophic loss, the Indians of Wellesley and Natick endured, going on to serve with honor in the American Revolution, the Civil War, and beyond. Beginning in the 19th century and then on into the 20th, long dormant tribal councils re-formed and moved to secure rights long lost or challenged by encroachment. In our own time, kinship groups along with Native American writers and scholars are leading a re-interpretation of times long past.

Yet even in the midst of catastrophic loss, the Indians of Wellesley and Natick endured, going on to serve with honor in the American Revolution, the Civil War, and beyond. Beginning in the 19th century and then on into the 20th, long dormant tribal councils re-formed and moved to secure rights long lost or challenged by encroachment. In our own time, kinship groups along with Native American writers and scholars are leading a re-interpretation of times long past.

The Christian Commonwealth was no more, yet numerous stone monuments in South Natick attest to a community that stretched along the Charles River from Lake Waban to the Sherborn line. If stones could speak, what tales would they tell of those long ago days? ![]()

Across the Ages, The Spirit Endures

© 2011 Elm Bank Media | Beth Furman, Publisher | Beth@ElmBankMedia.com

recent comments