Xima Lee Hulings – The Making of an Artist

Xima Lee Hulings in her South End studio.

Haunting sepia portraits of ordinary people taken by Arkansas photographer Mike Disfarmer from 1910 to the 1950s cover Xima Lee Hulings’ South End studio walls. She has painted her subjects onto heavy watercolor paper and surrounded them with backgrounds from her imagination: gold leaf, bright William Morris wallpaper patterned floors, circles reminiscent of iconic Christian halos or Buddhist mandalas patterned behind some of their heads. Others have been trimmed with silk and appear to be ancient Japanese scrolls, until you look more closely.

“I’m from the south,” says Xima, a petite blonde artist from Atlanta who was transplanted to Weston in 2001. As if you wouldn’t know that immediately from her accent, her gracious manner, and her fourth-generation southern name. “I remember the way the south smells, the way the air feels, and the mindless chatter in the Piggly Wiggly. Disfarmer’s subjects remind me of home. I want to know them, not in his context but in mine. I’m fascinated by memory and how people use it.”

Xima was immediately taken with Disfarmer’s subjects when she found a book featuring his work in 2006. She explored his images through her paint brush by copying them in tempura—she loved the process of grinding egg into pigment with a stone. As she writes in her Artist Statement, “It wasn’t until I began working with egg tempura that something shifted in my relationship to his photographs.” She moved on to acrylic ink “to scratch the surface, looking for information,” and, more recently, to watercolor. From there her work took flight.

Where does her irrepressible creativity stem from? “It probably all goes back to my mother,” she says. “Today if I call her she might say ‘I’ve just painted the staircase purple.’ She was a concert pianist. I remember her in sequins, stiletto heels, and glittery gold.”

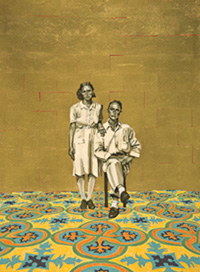

“Stand by your man”, 2009, 10″ x 14 1⁄2″, ink/gold leaf on paper

Xima’s childhood bedroom in Atlanta had a pitched ceiling and yellow wallpaper. “Wallpaper,” she said, “became the constant witness to all the things that changed in our lives.” She remembers that her grandparents’ house was used as a hospital during the Civil War and that some of the patients carved their initials on the window frames—they wanted to make their mark. Xima never forgot those initials. At ten she decided to be an architect. Her Tennessee grandmother took her seriously: she gave Xima a subscription to Architectural Digest, and a set of drafting tools.

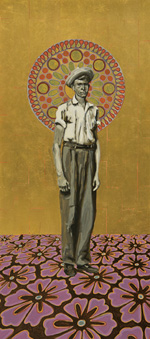

“Daisy”, 2009, 5 7⁄8″ x 12″, ink/gold leaf on treated gesso board

When, in 1988, Xima earned a Master’s degree at Columbia Architectural School, a world of mentors opened up. Klaus Herdeg, her professor of Islamic Architecture used to say to her, “you only see with your western eyes,” which stopped her in her tracks and forced her to look more closely. Herdeg also introduced her to Louis Kahn, who became a pivotal mentor with his famous words, “nothing new has ever been created.” He thought of art as a living changing thing. When he built the British Art Museum, the foundation cement cracked, but Louis Kahn wouldn’t let the workers correct it, he said “leave it—that’s the life of the building.”

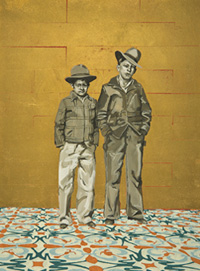

“Tough guys”, 2009, 9″ x 12″, ink/gold leaf on paper mounted to board

That same year Xima Lee married Willis Hulings and they moved immediately to Japan. Yoshio Taniguchi, the architect who transformed New York’s Museum of Modern Art, hired her to work in his office. After grumbling that he’d never hired a woman before, he too turned out to be an important mentor. He taught her how to edit. It’s just as important, he told her, to learn to live with what you cannot do, as to concentrate on your strengths. She landed in an art class in Tokyo that taught painting the classic way: examining great works of art and copying them in your own style. “You have to repeat to see where the pattern is,” she explains. “Patterns simplify nature.” She searched the Tokyo Museum to find a 13th century horizontal scroll called The Burning of Sanjo Palace that she remembered from a History of Art class in college. She studied Japanese portraiture, iconic imagery, and gold leaf. Japan, she also learned, is about fleeting things, cut flowers, birth, life, and death.

“Stretch”, 2009, 9 3⁄4″ x 21 3⁄4″, ink/gold leaf on paper mounted to board

The year her father died, 2001, Xima says, “art saved me.” She moved to Weston with her family, and her husband encouraged her to go back to school. She enrolled in a Diploma Program at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and there, waiting to blow the lid off Xima’s artistic consciousness, was Professor Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons. “Don’t tell me the story, show me the story,” Magda counseled her. Xima had been struggling most of her life to paint perfect pictures, but Magda taught her that painting can be any combination of materials. “Go to CVS and come out with all the things you might need,” she said.

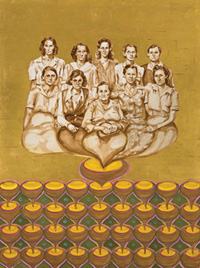

“Mama”, 2010, 18″ x 24″, watercolor/gouache/gold leaf on paper

Xima came back with pins, ribbons, sequins, nails, paste, glue, and more, with which she created Queen Bees, a painting made up of nine separate squares, each 10” x 10,” and each a representation in mixed media of an important woman in Xima’s life. In one, a photograph of her mother is cut into sections; the background includes flexible wire, copper nails, and ribbon. In another, small photographs of her little sister’s face are partially covered with a sequin web created with plaster and gauze. In 2004 Queen Bees was chosen to be in Boston University’s Sherman Gallery show titled “Keepsake: A Juried Exhibition of Work Using or Inspiring Found Images.” That piece opened the floodgates of Xima’s innate creativity. There is no stopping her now.

Her latest body of work, Disfarmer: Painted Series, Xima claims “is clearly driven by the genius of Mike Disfarmer.” Maybe so, but its success is due to Xima Lee Hulings’ undeniable inventive genius. Conceived by leafing through a book in 2006, her series traveled to Hot Springs, Arkansas’s Museum of Contemporary Art for its opening show in 2009. One portrait, Mr. Peacock,was chosen to stay there on permanent loan. Paintings from the Disfarmer series have become part of collections all over the United States.

What will she do next? Xima fixes me with her bright quizzical gaze, “I have the kernel of a new idea. I’m going to build houses for these people.” ![]()

© 2011 Elm Bank Media | Beth Furman, Publisher | Beth@ElmBankMedia.com

recent comments