The Legacy of Nelson McNutt

Diane Speare Triant writer

Patrick Collins photographer

“There were just a lot of old things left inside: glass marbles, dresser sets, lots of Bibles, stamps from Cuba, a collection of canes, 78-rpm records, many old tools and musty books-not in very good shape because the place had been left unheated.” So describes the first impressions of Dr. Richard Ulbrich as he inspected the inheritance he received from a newly departed friend. Ulbrich, a Wellesley orthodontist, became the owner of a 1930s four-room farmhouse in Weston, where his dear friend, centenarian C. Nelson McNutt had lived.

“There were just a lot of old things left inside: glass marbles, dresser sets, lots of Bibles, stamps from Cuba, a collection of canes, 78-rpm records, many old tools and musty books-not in very good shape because the place had been left unheated.” So describes the first impressions of Dr. Richard Ulbrich as he inspected the inheritance he received from a newly departed friend. Ulbrich, a Wellesley orthodontist, became the owner of a 1930s four-room farmhouse in Weston, where his dear friend, centenarian C. Nelson McNutt had lived.

On closer inspection, though, an old box-long forgotten in McNutt’s ramshackle cabin-turned out to be no less than a time capsule of America’s history.

“They were in a shoebox in a dresser drawer,” says Ulbrich. “A bundle of letters and documents tied up in a ribbon.” When Ulbrich untied the ribbon and unfolded the correspondence, he discovered an intriguing array of characters telling stories of the nation’s history through the written word.

“They were in a shoebox in a dresser drawer,” says Ulbrich. “A bundle of letters and documents tied up in a ribbon.” When Ulbrich untied the ribbon and unfolded the correspondence, he discovered an intriguing array of characters telling stories of the nation’s history through the written word.

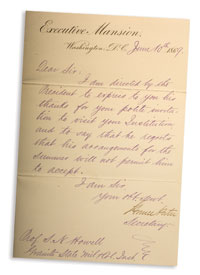

A 1918 letter stamped by the US censor from a World War I navy pilot in the Atlantic describes his ship vibrating as it fires shells on a German submarine; an 1895 Middlesex Mutual homeowner’s policy ($32.50 premium) offers insurance on the house, the barn, and the horse; an 1869 note on Executive Mansion stationery conveys regrets to a speaking invitation, via his secretary, from President Ulysses Grant; an 1815 British document certifies that one William Bartley, age 15, has served on “his majesty’s ship ‘Majestic’” and is thereby entitled to “share in all captures.” And, tucked into an 18th century Bible, the last will and testament of Elias Rogers, “of the province of New York,” which sets forth bequests in impeccable script, is dated a pre-revolutionary September 19, 1774.

“There were also everyday things,” says Ulbrich, pulling out penciled cards with 1940s recipes for Daffodil Cake and Almond Silver Cake {see sidebar}. “Here’s a hand-written cough remedy: “Boil one ounce of flaxseed in one pint of water. Add a little honey, rock candy, and juice of three lemons. Let boil well. Take one tablespoon three times daily, hot.”

“And they all had autograph books,” he continues, displaying McNutt’s mother’s leather-bound volume, hand-tooled with gold-tipped pages and beautiful engravings. “When people came to the house, she’d have them sign her book: ‘For age and want, save while you may, no morning sun shines all the day. October 2, 1893.’”

“And they all had autograph books,” he continues, displaying McNutt’s mother’s leather-bound volume, hand-tooled with gold-tipped pages and beautiful engravings. “When people came to the house, she’d have them sign her book: ‘For age and want, save while you may, no morning sun shines all the day. October 2, 1893.’”

For Ulbrich, though, what matters most is not the ink and paper Nelson McNutt preserved, but a desire to carry on in the tradition of the quirky gent he befriended 25 years ago. “I was driving by one winter in the 1980s and Nelson was shoveling out a bank of snow using one of those old wooden shovels,” Ulbrich says. “I had a plow and told him I’d give him a hand. I found him to be a wonderful, knowledgeable man, a link from the present to the past-someone who always had an answer when you had a problem.”

“When I helped him with his garden, it became the center of our friendship. He’d start the tomato seeds in his home. He could grow just about anything-sweet potatoes, peanuts, even mangels, a low-grade sugar beet that his uncle used to feed the cattle.”

McNutt, who died in October 2004 at age 105 on the very acreage where he was born in 1899, grew up on his grandfather’s 52-acre farm that stretched into Wellesley, living off the land with his parents and four sisters. His portion of that farm was the 2.97 acres at the intersection of Weston’s Glen Road and Oak Street where he built his house in 1935. Ulbrich is now working diligently to honor McNutt’s memory there. “Nelson told me that he thought I could always have a nice little farm here, so we had a big garden this summer,” Ulbrich says. “And I plan to put up a small post-and-beam house with a barn-that kind of flavor É It would make Nelson happy.”

Indeed, McNutt said he was happiest when “poking around” his corner-lot garden, which often doubled as a conversation center. Commuters crossing to the Mass Pike, grandnephews visiting from other towns, or neighbors returning home would stream in to chat, unable to resist McNutt’s plaintive wave or the sign proclaiming his latest birthday. He loved talking to them about the First Lady-no, not Laura Bush, but Eleanor Roosevelt! “Franklin could boss the world, but he couldn’t boss her,” McNutt would inform his little audience, chuckling.

Indeed, McNutt said he was happiest when “poking around” his corner-lot garden, which often doubled as a conversation center. Commuters crossing to the Mass Pike, grandnephews visiting from other towns, or neighbors returning home would stream in to chat, unable to resist McNutt’s plaintive wave or the sign proclaiming his latest birthday. He loved talking to them about the First Lady-no, not Laura Bush, but Eleanor Roosevelt! “Franklin could boss the world, but he couldn’t boss her,” McNutt would inform his little audience, chuckling.

One such passerby from Byron Road, Dr. Athena Papas, remembers McNutt as a neighborhood favorite. “We would all stop and talk with him,” she says. “We were his support system, and he a symbol of our Weston heritage.”

McNutt’s voice, which carried a Yankee inflection, still rings strong on a tape from a 2002 interview. His bygone vocabulary where paved roads are “macadamized” and porches are “piazzas,” and his nearly extinct accent that renders horses “hawses,” and tomorrow “tomorra,” transports listeners through a life that touched three centuries.

“In World War I I got drafted but didn’t get called because the armistice was signed,” he says in the 2002 taped interview, explaining how he was drafted into both world wars. “In World War II, I went from here to Camp Devens. From there to Missouri. From there to Salt Lake City. I got discharged in Spokane, Washington. After that, I never left Weston. I figured the devil you know is better than the one you don’t know.”

Lucid and feisty until the end, the rail-thin centenarian who merrily attributed his longevity to “never getting married or going to a doctor” lived alone and simply, using a dial telephone, a free-standing sink, and a backyard well. A rascal with an eye for the ladies, McNutt’s philosophy was to enjoy the present. “I just live from day to day,” he said. “I don’t know anything about tomorrow.”

Lucid and feisty until the end, the rail-thin centenarian who merrily attributed his longevity to “never getting married or going to a doctor” lived alone and simply, using a dial telephone, a free-standing sink, and a backyard well. A rascal with an eye for the ladies, McNutt’s philosophy was to enjoy the present. “I just live from day to day,” he said. “I don’t know anything about tomorrow.”

He was sometimes spotted with his friend Fred Campbell of Glen Road taking spins in his first car, bought in 1920, a Model T Ford “depot hack” wagon. “Nelson soon sold the wagon to his sister, Ella,” Campbell says, “because it didn’t afford enough privacy when he took his girlfriends out!”

The Model T languished in a shed for 60 years, until Ella gave it to Campbell in appreciation for neighborly help through the years. “We had it running within a couple of hours,” Campbell recalls. “I still have it. They have an antique car show in Weston. If nothing else, we usually get a prize for being the oldest one.”

When riding with Campbell, McNutt would putter past the luxury cars and stately homes of his neighbors, content in his wood-paneled time machine, thinking back:

“In 1905, when my grandfather, George Wyman, died, there were gravel roads,” he would say, his memories marching in review like a parade of toy soldiers. “There were no macadamized roads in Weston. And no fire department. Only horses and one thing and another. There was lots of cultivated land. You can see now through the woods where the stone walls were. I went to the one-room schoolhouse. In those days we all drank out of the same pan with a long-handled dipper, and we had no telephone, no electricity and a little two-holed outhouse.

I remember the dirigibles and the Stanley Steamer, made in 1903 in Newton,” he continues. “You had to steer it with a stick attached to the front wheel É And I knew Mabel Page’s brother. Her murder on South Avenue (Route 30) was my first memory.” [The trial of Page’s 1904 stabbing stands out for its death-penalty verdict based on circumstantial evidence.]

McNutt held down several lifetimes’ worth of jobs in his 105-plus years. He was a water tester at Norumbega Reservoir for three decades. He was also a chauffeur, gardener and woodchopper for wealthy neighbors bordering his family’s farmland. He cut pond ice for two paper-company magnates-Charles Dean and Garret Schenck-who owned “half a pond each” and had personal icehouses. After a day of ice-chopping, McNutt tells of putting his feet up on the stove in agony, “popping chilblains [blisters from exposure to cold] with a stick.”

McNutt first voted when Woodrow Wilson was president. “While I was voting,” he says, “I remember that this old fellow of 75-a selectman or something-had a cigar in his mouth and was going like this, blowing smoke rings up at the ceiling É I also remember a one-eyed fellow down the street. He’d been hit with a pellet stealing a pig during the Civil War.”

McNutt never mentioned, though, his own connection to the Civil War through his great-uncle, John Black, and his first cousin once removed, Willie Black, who fought together as Union infantrymen. Their letters to McNutt’s grandmother, Hannah Black Wyman, written from Civil War battlefields, the names of which today are ingrained in most middle-schoolers’ minds, are among the 1860s trove that McNutt squirreled away.

McNutt never mentioned, though, his own connection to the Civil War through his great-uncle, John Black, and his first cousin once removed, Willie Black, who fought together as Union infantrymen. Their letters to McNutt’s grandmother, Hannah Black Wyman, written from Civil War battlefields, the names of which today are ingrained in most middle-schoolers’ minds, are among the 1860s trove that McNutt squirreled away.

One post from Willie Black is dated October 19, 1862: “Dear Aunt Hannah We are now encamped in a beautiful little valley near Harper’s Ferry. We were in the late battle of Antietam and our regiment was badly cut up but John and I escaped without a scratch.”

John Black, though, was not so fortunate in the end. Having survived captivity in the notorious Southern prison, Andersonville, he wrote these words in April 1865 to his twin sister, Hannah, from a New York military hospital: “Dear Loving Sister É My lot is a hard one. I hope that you will never suffer as I have, but I ham [sic] as well as I can be until I have my legs taken off. I dunot [sic] know when they will take them off but I hope that it will be soon, for I want to get home once more and see you all if it is God’s will.” Two days later, Black died.

One Wingate Chase writing from Silver City, Nevada, however, viewed the Civil War as but a distant curiosity next to the realities of life in the Wild West: “August 14, 1861… You ask if we hear anything about war in this part of the world. The Pony from the East goes through here twice a week É I should like to have money enough to go and see this war É We have about 1500 inhabitants in this place and they kill from one to three men a week just as the excitement runs. They get round in the saloons and get to talking politics and secession and the first thing you know out comes their revolvers and they are shooting away.”

Ghosts from other decades also haunt McNutt’s dilapidated chambers with their written words. One righteous gentleman in 1879 pens lawyers with a request to represent him as a claimant to an entire city block of Chicago’s Washington Square! “My grandfather was street and canal contractor for the city of Chicago, when that city first started,” he writes. “He took in part payment for his services two blocks of land. One he sold, the other É is my claim.”

A loving daughter labels an envelope “from Mama’s 1853 wedding dress,” in which a scrap of jade-green silk is preserved.

And Weston shoemaker, Amos Wyman, McNutt’s ancestor on Mary Wyman’s (McNutt’s mother) side, leaves a 38-page ledger of his accounts in such precise order that one expects him to be penning in the next entry at any moment, rather than two centuries ago. “April 28, 1803,” he writes, the ink now smoky, “for Samuel Kendal, one pair of Calf skins shoes, $2.00.”

The ledger, the letters, the autographs, the 1920 “woody” wagon-still in pristine condition in Campbell’s shed-are a bountiful legacy from the colorful centenarian who never really quite died.

“Nelson waited for Fred Campbell to come down from Maine to say good-bye,” Ulbrich says, describing the final hours of the friend and father figure he had befriended and loved for 25 years. “He thanked me and the women aides for taking care of him; he gave my wife, Dede, a big kiss-as usual, never on the cheek! And then, he just wore out.”

recent comments