Miguel Gómez-Ibáñez

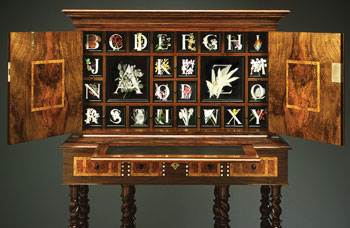

Alphabet Desk by Miguel Gómez-Ibáñez

Miguel Gómez-Ibáñez was walking by the Boston Architectural Center on Newbury Street one day when an exhibit of furniture made by students from the North Bennet Street School caught his eye. He recalls thinking, “If I could do something like that, I could feel accomplished.” It was 1996 and Gómez-Ibáñez was running his own architectural firm. Its success kept him focused on his clients’ and employees’ satisfaction, leaving him two steps removed from the work he loved.

With his family’s encouragement, Gómez-Ibáñez decided to take a two-year hiatus from architecture to attend North Bennet Street School (NBSS). Once there he realized that furniture making was more a part of him than architecture. “I couldn’t stop doing it,” he says. “It changed me.” After graduation Gómez-Ibáñez, a Weston resident since the 1970s, set up a studio in Waltham and soon was nationally recognized for designing and making traditionally inspired, exquisitely crafted furniture. His work has been exhibited nationally and his articles and essays have appeared in woodworking and craft publications as well as House & Garden and Good Housekeeping magazines. Gómez-Ibáñez has also served as president of the Furniture Society of America for four years.

A group of students at North Bennet Street School, circa 1910

“My clients provide the challenge,” he says. “One might have a bedroom with two real Portsmouth dressers and need a pair of side tables that can hold their own. Another might commission a set of dining room chairs elegant enough for their Greek Revival home.”

Four years ago following a national search, Gómez-Ibáñez was asked to become the sixth president of the NBSS, and today he is willingly back at a desk much of the time. NBSS is the oldest craft university in America and is located in its original five-story brick building at the corner of Salem and North Bennet Streets in Boston’s North End. Gómez-Ibáñez’s office is in one of two adjoining townhouses acquired in 1999 and renovated by NBSS craftsmen.

NBSS offers instruction in eight trades: bookbinding, cabinet and furniture making, carpentry, jewelry making and repair, locksmithing, piano technology, preservation carpentry, and violin making and repair. Hand skills are emphasized and evolving technology is incorporated. The school’s stated goal is “to provide exceptional preparation for careers that employ the intelligence of the hands to produce objects that last.”

Like Gómez-Ibáñez, many students experience NBSS as a transformation. He says, “Students often share with me their ‘Aha!’ moment when they see a violin or a piece of furniture or visit our locksmithing department and realize that that is what they want to do. It’s no longer an interesting idea, it‘s something they absolutely have to do.”

A group of students at North Bennet Street School in 2010

NBSS has 160 full-time students, and 500 to 600 attend part-time, in evening and weekend workshops. Students come from varied backgrounds but the typical student, if there is one, is a 32-year old career-changer. Men and women are equally represented. “It’s amazing to me that people from so many backgrounds can coalesce around working with their hands. They’re urban and rural, rich and poor, and from all kinds of geographic origins.” In contrast to what Gómez-Ibáñez calls today’s “distributable knowledge,” at NBSS instructors teach by example and students learn by trial and error.

Pauline Agassiz Shaw (1841 – 1917) founded NBSS in 1885 to teach immigrants a trade and to care for their children. She moved to Boston from Switzerland in 1846 with her family, and her father, the naturalist Louis Agassiz, became professor of zoology and geology at Harvard. After the death of Pauline’s mother Cecile, Agassiz married Elizabeth Cabot Cary who became the first president of Radcliffe College for women. Pauline married the financier Quincy Adams Shaw in 1860 and devoted much of her family’s wealth to establishing and supporting neighborhood houses in Boston that included kindergartens, schools, and social service programs.

In 1891 Pauline brought Gustaf Larsson from Sweden to establish the Sloyd method of teaching at NBSS. Based on “the intelligence of the hands,” Sloyd uses project-based, craft training to develop academic competence and character. At NBSS, the North End’s first community center, health service, and branch of the public library were established and later turned over to the City of Boston.

North Bennet Street School offers instruction in eight trades including violin making and repair.

Gómez-Ibáñez is uniquely qualified to lead NBSS as the school considers the possibility of a new home in the North End. If it happens, this move, the first in 125 years, will be emotional for many. However, bringing the carpentry and restoration carpentry departments back from rental space in Arlington and gaining up-to-date classrooms and workshops, a lunchroom, and a space for the entire school to convene, are important needs to address.

Gómez-Ibáñez laments today’s trend in eliminating public school programs that involve handwork. “Many parents think shop or woodworking won’t help kids get into college or excel on the computer, but studies have shown that handwork improves academic intelligence and performance,” he notes. Where else do kids today get the chance to see how things are put together? So much of what we use is disposable or can’t be taken apart and tinkered with.

William and Mary Highboy

Under Gómez-Ibáñez’s leadership, NBSS has returned to educating neighborhood children. In 2009 NBSS re-established a program first begun in 1894 that brings middle school students from the John Eliot K-8 School in the North End to NBSS for woodworking lessons. All students attend weekly; special needs and abilities are blurred by the challenges of the curriculum. “It’s important to experience alternate paths,” he says, “and to know that you don’t have to be a doctor, lawyer, or Indian Chief. These youngsters love seeing the possibilities.”

Gómez-Ibáñez’s contract allows him to spend one afternoon a week in his studio in Waltham. His current project is a wedding chest for his godson, Adam Hyde, who lives with his wife and son in Washington State. Inspired by a carved oak Pilgrim chest from the 1600s, the blanket chest is made from a maple tree felled on the Wellesley Street property where the young man grew up. Altogether Gómez-Ibáñez will make five chests, including those for his children Daniel and Sara Gómez-Ibáñez and his stepdaughters Julia and Brooke Chandler. Gómez-Ibáñez is married to Fay Larkin.

Miguel Gómez-Ibáñez (right) assisting a student.

Brian Holt of Weston, retired COO of Thermo Electron and currently a trustee of NBBS, is a graduate of the carpentry department. He says, “Miguel has done a great job. The school is on solid footing despite the tough times of the last two years.” Holt encourages people of all ages to tour the school, take a workshop, visit the gallery store, and discover ways to get involved.

Much of Gómez-Ibáñez’s work resides in homes on Beacon Hill. A gallery bench commissioned by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum can be found there. Two signature pieces, the Alphabet Desk and the William and Mary Highboy, are located in Weston. Made from woods like cherry, walnut, Carpathian elm, and burled oak, these pieces show Gómez-Ibáñez’s mastery of design, love of architecture and history, and commitment to craftsmanship. At the helm of NBSS and in his studio, Gómez-Ibáñez continues the legacy of Pauline Agassiz Shaw’s remarkable vision for learning and for life. ![]()

Brian Kelly, Technology and Engineering Teacher, Wellesley Middle School

© 2010 Elm Bank Media | Beth Furman, Publisher | Beth@ElmBankMedia.com

recent comments