The Other Emma Stone

The Other Emma Stone

Alden Ludlow, grant-funded Archivist

August 20, 2018

Academy Award winning actress Emma Stone may be all the rage in Hollywood these days, but a century and a half ago a different Emma Stone, of Wellesley, was the apple of her father’s eye.

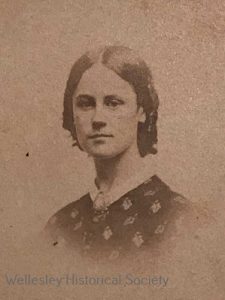

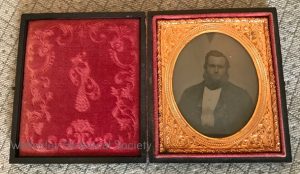

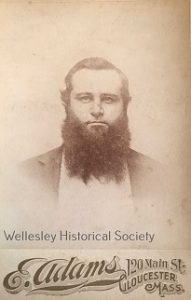

At the Wellesley Historical Society, processing archival collections and preparing them for research access can lead in unexpected directions. Recently we received a family collection assembled by Christine Barnes, a lifelong Wellesley resident who passed on in 2015. The collection contains much interesting material, including a set of correspondence between her great-great-grandfather Daniel Stone Jr. and his daughter Emma Stone, Christine’s great-grandmother. In addition to the letters, the collection contains photographs of Daniel and Emma.

Emma Stone was born in Grantville, what is now Wellesley Hills, in 1848, the first of three daughters to Daniel Stone, Jr. and Mary Elizabeth (Chapin) Stone. According to Wellesley historian Joseph E. Fiske, Daniel Stone owned the Elm Park Hotel from 1845-1851, though it is not clear whether it was Daniel junior or his father who owned the property, which stood near the Clock Tower in Elm Park until 1908.

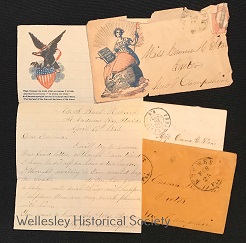

Another mystery is that at some point the family moved to New Hampshire, where, by 1861, Daniel either volunteered or was conscripted into the Union Navy, where he served on the U.S. Bark Roebuck sailing out of Portsmouth. We have a letter addressed to Emma from Grantville dated 1861, at which point she was in New Hampshire with her mother and sisters. That letter is the first in a series of letters in which Emma and her father begin a lengthy correspondence.

From that initial letter onward, Daniel’s letters to his daughter originate from the Roebuck, which served as a notable blockade ship for the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, serving in the Union Navy’s East Gulf Blockading Squadron. Most of the Roebuck’s mission was to blockade supplies coming into Confederate ports in the Gulf of Mexico, particularly in the area of St. Andrew’s Bay, in the Florida panhandle. The official actions of the Roebuck are well documented in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I, Volume 17: East Gulf Blockading Squadron, held in the Library of Congress.

From that initial letter onward, Daniel’s letters to his daughter originate from the Roebuck, which served as a notable blockade ship for the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, serving in the Union Navy’s East Gulf Blockading Squadron. Most of the Roebuck’s mission was to blockade supplies coming into Confederate ports in the Gulf of Mexico, particularly in the area of St. Andrew’s Bay, in the Florida panhandle. The official actions of the Roebuck are well documented in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I, Volume 17: East Gulf Blockading Squadron, held in the Library of Congress.

What is clear in the correspondence is that Daniel had great love and high expectations for his daughter, even at a  young age. He was proud that she was attending high school, and was equally impressed with her writing, though we currently have no letters surviving that she sent to him. He repeatedly stresses her role as the oldest sister, noting, “Emma, be a good kind Girl to your Mother and Sisters, and remember you are the oldest sister and the younger ones will look to your behavior as an example for them.”

young age. He was proud that she was attending high school, and was equally impressed with her writing, though we currently have no letters surviving that she sent to him. He repeatedly stresses her role as the oldest sister, noting, “Emma, be a good kind Girl to your Mother and Sisters, and remember you are the oldest sister and the younger ones will look to your behavior as an example for them.”

“I expect you have got quite a string of Beaus by this time,” he notes in one letter; chiding her about her suitors was one of his favorite topics. She was 13 at the time. In another letter he admonishes her for bringing her sisters to the circus, but changes his mind, writing, “I can see no harm in it if people know how to conduct themselves … But still I think it wrong to make a practice of visiting such places too often. Once in a while I think it a benefit to people of a certain age, as it gives them a chance to see what is going on in the world.”

But the news was not all Beaus and circuses. He tells tales of the ship’s crew and missions, noting details about Confederate actions and the Roebuck’s responses. He lauds the Roebuck’s “rifled cannons.” His 1863 account of destroying the Salt Works at St. Andrews, and the ship taking on the freed slaves who had worked there, is riveting; seven of the freed slaves took on the last name Roebuck to honor their new-found freedom.

He repeatedly notes the incessant “mosquitoes, which act as though they would eat us up alive.” In one letter he sends home a Confederate ten-dollar bill: “I got it off one of our prisoners … I want to keep it as a curiosity.” Many of the letters have their original envelopes, bearing postmarks from Key West and Tampa.

He repeatedly notes the incessant “mosquitoes, which act as though they would eat us up alive.” In one letter he sends home a Confederate ten-dollar bill: “I got it off one of our prisoners … I want to keep it as a curiosity.” Many of the letters have their original envelopes, bearing postmarks from Key West and Tampa.

Daniel never made it home to Emma and the rest of his family. He died in 1864 at Egmont Key, near Tampa, just before the Roebuck returned to Portsmouth at the close of the war; to this day Egmont Key is a remote, inaccessible place. Records indicate that the Roebuck had been struck by Yellow Fever toward the end of its deployment, so it is possible he succumbed to that disease. From a historical perspective, it is saddening to note that Emma’s correspondence was likely lost upon his death.

Emma would go on to marry Alfred de Rochemont, of New Hampshire, in 1865; she was 17. At some point after their marriage they moved to Grantville, a sort of homecoming for Emma. Alfred and Emma had two daughters, Eva and Ella Mae; Ella Mae would marry Shelley Denton, the son of William Denton, while Eva would go on to marry William Butman; Christine Barnes, the creator of this collection, was their granddaughter. Emma died in Grantville in 1884.

With this collection, the Wellesley Historical Society holds a substantial number of Civil War era letters from father to daughter, while the father was serving in the Union Navy on the U.S. Bark Roebuck with the East Gulf Blockade. These types of Civil War letters are an important source for historians researching military and social history of that period. This type of material sparks interest in archival collections not just on a local level, but on a national level as well, and are also of interest to African Americans piecing together their more elusive history and genealogical work.

The Christine Barnes Family Collection has been preserved and made accessible with generous grant support from the Wellesley Community Preservation Commission (CPC).

recent comments