If Stones Could Speak

Peter Golden writer

Peter Baker photographer

The epoch of the Native American hunter-gatherers who called Wellesley home in the years prior to the arrival of the Puritans in 1630 is long gone, yet the notion of turning back the clock in order to understand the lives of Wellesley’s first residents is an intriguing one.

“I’m interested in Native American culture and language,” says Joel Slocum, a member of the Wellesley Historical Commission, “and the contribution Indians have made to our lives. There are all those fascinating names,” he adds, referring to the hundreds of native place names that dot the New England landscape.

“You get hooked; how can you not?” asks long-time Wellesley resident Ann Schaller, who along with husband Fred has devoted much of her life to assembling a wide-ranging record of local history. “We built a tremendous archive and research library; it was my proudest achievement,” she says, recollecting her decades of involvement with the Natick Historical Society, where artifacts and records relating to Wellesley as well as Natick are stored in a small museum by the Charles River.

Wellesley’s primordial past was complex and fascinating. But before we consider it, let’s pause for a moment and tip our hats to local historian Beth Hinchliffe, whose Five Pounds Currency, Three Pounds of Corn – Wellesley’s Centennial Story, is well known to many residents. Masterfully written, it consolidates the whole span of town life from early colonial days up to 1981. But Hinchliffe’s graceful, wonderfully detailed narrative and informed choice of images is only partly concerned with the colonial period. And while it makes reference to Wellesley’s pre-colonial past in its opening pages, it moves quickly into more recent days in order to relate the full scope of town history.

Lake Waban

But strip away the centuries since the arrival of the first Europeans, and Wellesley history goes back farther than you might imagine. When, precisely, the area was first settled is hard to say, but there is no doubt—fables of Vikings or Irish monks notwithstanding—that Wellesley’s first residents were Paleo-Indians.

Three Villages

Historic accounts note there were at least three Indian villages here, long before Europeans ever dreamed of the New World. Notably, significant artifacts associated with Wellesley’s Native American past have been chronicled, but are hard to locate, in large part because 19th century farmers did not recognize the significance of the objects they discovered in their fields. And while no definitive Carbon 14 dating exists in the immediate area of the town, the landscape and some written history still provide tantalizing glimpses into the past.

A path and a river defined this place. The “Natick Road” led from a large Indian village called Nonantum high above the Charles River near present day Newton Corner. Washington Street follows the original route to Lower Falls; where high on a bluff above the Charles River sat another substantial Indian village called Coowate.

In those long-ago days the river teemed with fish, providing ample food for the large settlement. For Native Americans living to the east and migrating to winter hunting grounds, Coowate was the first stop in what would become modern-day Wellesley.

Further along the Natick Path was a widely dispersed settlement, one end of which was on the Charles, which the Indians called Quinobequin or “the river that turns on itself.” There, a sachem (leader) named Nahaton lived with his band in the area now known as Upper Falls. Cornfields separated it from three peaks to the west known four hundred years ago as Maugus, after the sachem that dwelled with his band at their base near present-day Longfellow Pond. The area is now called Wellesley Hills. Both Nahaton and Maugus sold large tracts of their land to the English in 1680, leading to the establishment of what would later become modern-day Newton and Wellesley.

Lower Falls

Further west, the road from the “Great Plain,” (Route 135 through present day Needham) intersected with the Natick Path just east of the Wellesley Free Library. It led from another Indian settlement near Needham’s present-day Ridge Hill Reservation.

Archeological Evidence

Continuing along the Natick Road (now called Route 16), one passed Lake Waban and then came to the waterfalls at Natick, which in an earlier age was part of Dedham. The area around the lake was included in Natick, but is now part of present-day Wellesley. At the falls, substantial archeological evidence confirms Native Americans were settled for millennia before the arrival of Europeans.

In the 1650s Nahaton and Maugus, along with the Massachusetts Indian leader Waban, settled at Natick, following the call of a Puritan minister named John Eliot. All three, along with scores of other Native Americans, sought salvation from a god other than the traditional deity worshiped by Native Americans.

Eliot’s intention was to create a utopian Christian-Indian community at Natick. He was nothing if not energetic and soon Natick became headquarters for a network of almost twenty “Praying Indian Towns” in the region. In our own time those communities bear names like Ashland, Hopkinton, Upton, Littleton, and Chelmsford.

As noted earlier, the east end of the Natick Plantation was situated firmly in present-day Wellesley on Lake Waban. There, roughly two-dozen Native American families (of the approximately two hundred residents in Natick in the 1660s, at its most populous) made their homes, as can be clearly seen on a hand-drawn map dating from 1730 in the possession of the Natick Historical Society.

Waterfalls at South Natick

But that map is not the only artifact germane to this story stored in the fascinating little museum to which Ann Schaller has devoted herself. Recently, I undertook a visual review of archaic-period stone pestles there (for pounding ground nuts), as well as stone axes, scrapers, and flint arrowheads. When compared with similar, dated material in the collections of the Robbins Museum in Middleborough, Massachusetts there is little doubt of their similarity.

Local Origins

One cannot speak with certainty regarding specific dates according to Tonya Largy, an archaeologist who accompanied me to the Natick museum, but it is important to understand that Native Americans have been living here for thousands of years. The “founders” of the towns west of Boston, where Wellesley and Natick are situated, were Indians. Of that there can be no doubt.

For comparison, a site in Ipswich called Bull Brook has been positively dated to 9000 B.C. and another in Middleborough dates to 7000 B.C. A Wayland site has been dated to 3000 B.C. And further west, on the shores of Lake Champlain, archeologists featured in Wellesley resident and film producer Peter Frechette’s video series “Hidden Landscapes” have positively identified a Native American maritime culture dating to 13,000 years ago.

Spiritual Context

Wellesley’s Indian communities were also part of a larger context – one relating to matters of the spirit. In the culminating segment of Frechette’s video series, entitled “The Great Falls,” Native American preservationists along with academic archeologists and astronomers demonstrate clearly that natives in the indeterminate, pre-colonial past constructed a “sacred landscape,” stretching from present day Fort Drum near Lake Champlain to Turner’s Falls in western Massachusetts and on down through Upton and Grafton to Middleborough at Betty’s Neck – a major powwow site.

This “sacred landscape” (a kind of solar observatory) continues on to the Cape and Islands, even passing over the present-day site of a proposed offshore wind farm. Focused around observance of the Summer Solstice (the time for planting and a special day of observance in the Indian year), a series of cleft boulders, rock grottos, megalithic stone circles, and rock cairns highlight a fully evolved Native American civilization.

Elsewhere in New Hampshire and Vermont, Frechette and his senior partner, director Ted Timreck, focus their cameras on enormous stone platforms. Archeologists puzzle over their intended use, but point out they must be Native American in origin, for what Yankee farmer ever had the financial wherewithal or spare time to construct such megaliths?

Elsewhere in New Hampshire and Vermont, Frechette and his senior partner, director Ted Timreck, focus their cameras on enormous stone platforms. Archeologists puzzle over their intended use, but point out they must be Native American in origin, for what Yankee farmer ever had the financial wherewithal or spare time to construct such megaliths?

There is another aspect to Native American spiritual life worth noting: Everything is sacred; all of life and nature are imbued with meaning. Native Americans in ancient times worshiped the deity Manitou, the god with whom the missionary John Eliot was forced to contend in his efforts to convert Native Americans to Christianity.

Every aspect of daily life carried some form of spirit. Mary Concannon, an educator at the Robbins Museum, notes that even so trivial a creature as a rabbit was construed as an offering from the gods. In Concannon’s view, trees, fire, and the very ground under Native American feet were (and still are) “part of the circle of life, and sacred.”

A rare Observation

Frechette and Timreck, the latter of whom is a noted filmmaker associated with the Smithsonian Institution, have assembled decades of archival video to make their case. From their examination of dozens of archaic stone assemblages and archaeological digs throughout New England, they have come to a firm conclusion best paraphrased in the words of the Native American preservationist Doug Harris: Once pre-colonial Native Americans established a sacred site, it remained active, and is to this day, no matter how degraded by time or the depredations of those who have “borrowed” its elements (stones) to construct pasture or foundation walls.

And as the filmmakers clearly show, those sacred sites are located virtually everywhere in New England, as I could see last summer near the peak of a hill in West Natick. One can readily imagine Wellesley, too, has its stones – perhaps in your back yard.

And as the filmmakers clearly show, those sacred sites are located virtually everywhere in New England, as I could see last summer near the peak of a hill in West Natick. One can readily imagine Wellesley, too, has its stones – perhaps in your back yard.

Frechette, who continues to work on “Hidden Landscapes,” voices a certain level of frustration in dealing with the topic of pre-colonial Native Americans. “I think that my personal perception has gone from an afterthought, if I ever really thought about it at all,” he says, “to feeling some pain when I think of what was done to Native Americans and not just in Wellesley and Natick. The vanquishing of an existing society without a second thought and the destruction of what they had created gives me pause. The difficulty I have as a filmmaker in even convincing people that there was an advanced Native American culture here stems from the limited, almost non-existent evidence of their presence.”

The over 38,000 Native Americans living in Massachusetts share that frustration, according to Pam Ellis, a Nipmuc descendant of both the Nahaton and Speen bands. “There are six tribes in the state, two of which are federally recognized. We are still here – always have been, always will be.”

Redemption and Salvation

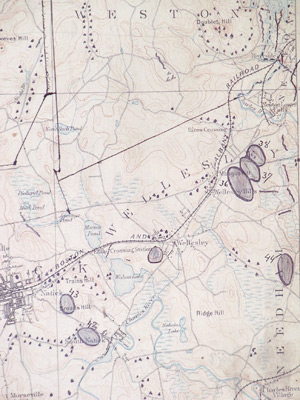

Prior to crossing the chasm of faith to Christianity, local Native Americans had their own sacred landscape, as can be deduced in Wellesley and its neighbors to the west, Natick and Framingham. The topography of all three places contains a series of hills of about 300 feet in elevation, as Adams Shipman of the Natick Historical Society has clearly shown. “I worked with a US Geological Survey quadrant map dated to 1877,” he says, “and found a succession of hills situated westward from Upper Falls and Maugus Hill to the Town Forest in Natick and beyond. Magus has been substantially altered, but plotting my way west, I readily could see Captain Tom’s Hill in Natick (current site of Jordan’s Furniture), Indian Head and the Mount in Framingham, and Nobscot Hill on the Framingham-Sudbury border.”

All of Shipman’s finds appear in clearly documented, 19th-century local histories and show evidence of substantial Indian settlement in prior ages. On them signal or sacred fires would be visible from one peak to another. All were linked (and still are) by established pathways (first trails, now roads and highways) that while known to us by familiar names like Washington Street (the Sherborn Road in earlier days) and Route 27 were in their time direct routes to Indian settlements. These included Nashoba (Littleton) and Musquetid (Concord), where Waban lived prior to coming first to Nonantum and then Natick.

Detail from a US Geological Survey map of 1877 shows Maugus/Wellesley Hills and other elevations to the west in Natick, including Trains Hill.

Wellesley/Natick was connected by geography – the river, which was a major source of food for Native Americans – trade paths stretching far into the interior, and a common spiritual culture in which hilltops played a role as lookout and signal fire sites. And fire, of course, was sacred.

Bounding and marking the sacred landscape for Wellesley’s Native Americans was the Great Blue Hill to the southeast, Mt. Wachusett to the west, and Mt. Monadnock (the hill that stands alone) to the north. The Great Blue Hill, which was of penultimate significance to local tribes, would have been visible from the top of Maugus Hill, the slopes of which, in pre-colonial times, would have been burned clear for corn planting, as well as for purposes of defense.

Marking Seasons

Ritual fires marked the seasons of a civilization that once occupied this land in a complex harmony with nature. When interrupted by the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, it suddenly faced a series of daunting challenges. At first, Native America adjusted to the presence of the English, but in 1675 a war broke out when a tribal alliance attempted to drive the Puritans into the sea. In that terrible conflict, known as King Philip’s War, the Praying Indians of Wellesley and Natick played a role that remains controversial to this day.

In an article to follow this one, we will attempt to discover the history of those times and events. If stones could speak some of the loss and pain, the hopes and dreams of those far off days might be better understood. But for now we must stand in awe of an epoch long vanished and a lost history that we are only now beginning to understand is our own.

Peter Golden writes about the American experience as viewed through the lens of local history.

© 2010 Elm Bank Media | Beth Furman, Publisher | Beth@ElmBankMedia.com

recent comments